In the booming lake port and industrial center of 1850s Chicago, a city burgeoning with opportunity and growth, a shadow of lawlessness loomed large. As the population surged, so too did the undercurrent of crime, seeping into the cobblestone alleys.

In this crucible, Allan Pinkerton, founder of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, established a pioneering security force, laying the foundation for modern private security and forever transforming the landscape of urban safety.

The Dark Side of Chicago’s Rapid Expansion

The village of Chicago was officially organized in 1833, with a population of approximately 250. Twenty-eight ballots were cast to elect town officials. Chicago was incorporated in 1837 with a population of 4,170. By 1840, the population grew to it had become a town and then a city with a population of 4,500. Ten years later in 1850, the population was 29,963.

By 1856, Chicago had over 80,000 residents, with more arriving daily by steamships, wagons, stagecoaches, and trains. For instance, the city was the hub of ten trunk lines, with 58 passenger trains and 38 freight trains arriving daily. It was said that the Illinois Central Railroad was the first great “St. Louis cut-off” — a trip that could made between Chicago and St. Louis in 24 hours. A few years later, that same trip could be made in 12 hours, helping Chicago earn its name “The Queen of the West.”

The city had also earned an unenviable reputation for crime as the one of “wickedest cities” in the country. Chicago and Cook County were infested with “bold thieves and cunning counterfeiters,” (“The Scotch” 1875). Burglaries and robberies were frequent occurrences. Other disturbances followed including riots, assaults, and social disorder.

The city prison was built to accommodate 200 prisoners.

Policing a Growing City and the Struggle for Order

From 1838 to 1854 the Chicago police department consisted of a small collection of ununiformed officers and part-time night watchmen to serve and protect the quickly expanding city, with varying results.

Just two years later, the city’s police force increased to 80 officers to accommodate the rise in population and crime, and was still outpaced, grappling with the increasing need for order amidst the turmoil. According to some historians, the police force were unwilling to conduct investigations or shadow suspected criminals outside their own jurisdictions (Smithsonian Magazine). Criminals were often not identified and could make a quick escape out of the city on a railcar, a steamer, or stagecoach headed west.

The people of Chicago were uneasy, watching crime rise in their city. Those who afford it, began hiring private police to protect their homes and businesses, not always with the intended outcome, such as extortion and special protection for special prices.

Allan Pinkerton: A New Kind of Lawman in the West

In the late 1840s, Allan Pinkerton was an intrepid barrel maker in Dundee, Kane County, IL. While searching for lumber on Fox Island, Pinkerton discovered a band of counterfeiters and proceeded to help take them down, launching his career as a detective. He was appointed as a part-time deputy sheriff for Dundee before becoming a Special Agent for the U.S. Post Office — it was typical for individuals to contract with the Inspection Service to assist in resolving particular criminal cases.

During this time, Pinkerton built a solid reputation as an investigator-for-hire. In 1853, Pinkerton was hired as a part-time deputy sheriff for Cook County. During the next two years, he often worked undercover on his own time in ferreting out burglars, thieves, counterfeiters, and other lawbreakers. The Mayor, the Clerk, City Council, Court Recorder, and the Prosecuting Attorney recognized Pinkerton for his vigilant service in the city, and they paid him $200 (about $8,000 in 2024) as compensation.

“…his first care was that justice should be satisfied…”

His no-nonsense and often gruff approach made him feared among criminals — leading to more than one assassination attempt. Pinkerton was a natural-born detective with a rare genius and extraordinary personality for the craft, indomitable willpower, unfaltering courage, and unswerving perseverance. Possibly his most prominent characteristic was his high sense of justice, and his first care was that justice should be satisfied.

On this point, he was uncompromising to the last degree, and on this point, Pinkerton resigned from public office in February 1855 and established the North-Western Police Agency, later renamed Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. The Agency’s initial service line was “general detective police business” in Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana and mostly included investigating crimes, notably train depredations.

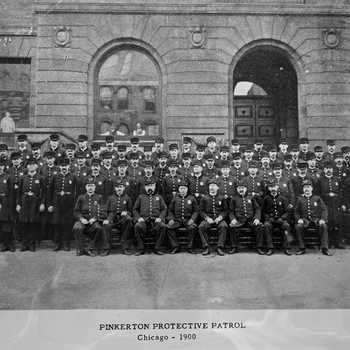

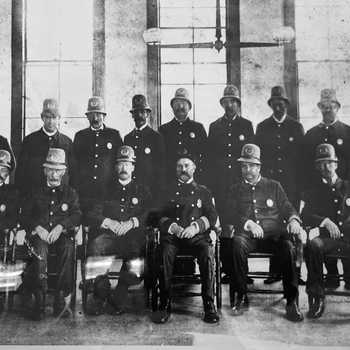

The Birth of the Pinkerton Protective Patrol

Not long after, Pinkerton created the Pinkerton Protective Patrol — also known as the Pinkerton Police Patrol, Pinkerton Preventive Patrol, and later the Pinkerton National Police Agency — a private police force that kept the city streets safe at night and provided night protection for partnering Chicago businesses., which included banks, shops and department stores, jewelry houses, and hotels. The PPP charged a standard price and offered the same unwavering service for every client. It is important to note that this was a uniformed police force, predating Chicago’s uniformed police force. Until 1858, the city’s police were plainclothes.

Pinkerton hired Paul H. Dennis — who later became one of Pinkerton’s Union Secret Service spies during the U.S. Civil War — as the first captain and six patrol officers selected for their general aptitude for police duty. They were incorruptible, strictly disciplined, experienced, and competent officers trained specifically for the patrol — developing a keen sense of observation for noting the passing of pedestrians, carriages, vehicles, and drivers, and reporting any changes, irregularities, or matters of interest on their beats.

They were prohibited from playing cards, dice, dominoes, or any game of chance while on duty. They were also asked to refrain from discussing religious or political topics at the station. (Always a good idea.) Officers were prohibited from drinking alcohol, smoking, and using chewing tobacco while on duty. And it was expressly noted that officers and personnel must not expectorate on the floor, or the radiators connected with the heating apparatus. (Again, always a good idea.) At all times patrol officers were expected to maintain their dignity without being harsh or using vulgar language.

“Officers were prohibited from drinking alcohol, smoking, and using chewing tobacco while on duty.”

Their uniforms were to be kept clean and neat and in good repair. Their shoes were polished before every shift, and their shields and buttons shined. Patrolmen were always identifiable as Pinkertons.

PPP personnel wore their uniforms at all times when on duty, unless exempted by the officer in charge for special reasons. Uniforms were kept in special lockers at the Pinkerton offices, and under no circumstances could uniforms be worn when off duty or removed from the premises. Pinkerton uniforms could not be stolen, replicated, or imitated.

The Practices of the Pinkerton Protective Patrol

As a former Chicago police detective, Pinkerton had a healthy respect for official law enforcement, advising his patrol personnel not to undertake any business that would interfere with municipal police regulations. They were instructed to use their best judgment without haste or prejudice, collaborating with and turning suspected persons over to Chicago police officers — either at the patrol station or meeting up with a beat officer. Under no circumstances, at any time, could Pinkerton patrol officers impersonate or claim to be deputy sheriffs, marshals, constables, policemen, or police Chicago police officers — unless they have been deputized and vested with such authority.

The legendary "Pinkerton Men" — so named even though a few undercover agents were women — were as integral to protecting the city as the official police. The patrol was responsible for 53 arrests in its first year.

“This force has become quite an institution…”

One client [Emma K. Parrish] wrote that their business was an early adopter of the Preventive Patrol, paying quarterly, and receiving reports from patrol officers if her employees “had forgotten to turn out the gas when locking up, and once when they forgot to lock up at all.” Of course, this business had not been a victim of burglary — they prominently displayed their “Protected by Pinkerton” placards in shop windows, effectively deterring criminals.

“Pinkerton’s Preventive police force, whose work is to guard the stores or merchants against burglaries and robberies. This force has become quite an institution, whose efficient services are highly valued,” (The Scotch is Chicago, Scottish American Journal, New York, Thursday, September 1875.)

If a crime did occur, Pinkerton and his detectives pursued the perpetrators beyond the city’s borders, tracking them to the Wild West and beyond, when necessary.

The Call of Duty

While patrol officers were designated as Nightwatch — divided into two shifts from 6 p.m. to 1 a.m. and 1 a.m. to 7 a.m. — they were alerted that they could be deployed wherever required, day or night.

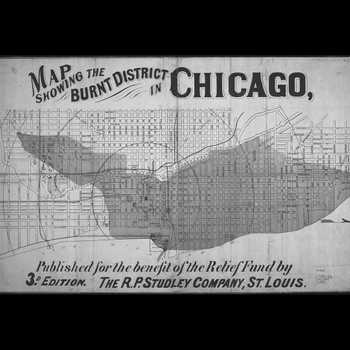

During the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, for example, the Agency’s patrolmen who at that time covered the greater part of the city, were on duty continuously while the fire raged for 30 hours, saving lives and protecting properties.

When the fire was finally extinguished — due to rain, Lake Michigan's barrier, and open spaces on the North Side, many of the patrolmen were off duty searching for their own families, some of whom had lost everything in the fire. (Pinkerton’s Chicago headquarters and all its contents were reduced to ash during the fire.)

The fire burned approximately 2,100 acres, or around 3.3 square miles, and destroyed about 17,500 buildings. In the wake of the disaster, the city turned to chaos. Mayor Roswell B. Mason declared martial law to preserve the peace and dispel civil unrest and tasked the PPP with patrolling the streets of the Burned District to prevent looting. Extreme consequences awaited those attempting to steal property or break open safes.

The Expanding Reach of Pinkerton’s Protective Patrol

As Pinkerton’s opened more offices and expanded across the United States, so did the Protective Patrol — although the beat patrols were mostly located in the Midwest. The PPP also began to take on more assignments such as protection for large events as well as requests for dedicated embedded protection — the first was Thomas A. Gallagher who traveled with the Barnum, Bailey & Hutchinson Circus [United Consolidated Exhibitors] starting in 1880.

The PPP was slowly disbanded over the years as efficient local police forces rendered private beat patrol service unnecessary. By the late 1940s, Chicago was the last remaining city with Pinkerton beat patrol, and that was discontinued in 1949. The Agency continued to provide uniformed private security services to protect property against fire, theft, and depredations at businesses, big circuses, colleges, universities, conventions, exhibitions, fairs, racetracks, athletic events, and other large public and private gatherings.

Always ahead of his time, Pinkerton knew crime had no boundaries. Not then. Not now.

WE NEVER SLEEP.

SOURCES

Alexander, Kathy. "Pinkertons." Legends of America, March 2024, www.legendsofamerica.com/pinkertons/.

Budhh, Aung. "The Great Chicago Fire 1871: Historical Photos That Depict the Destruction Caused by the Great Disaster." Bygonely, www.bygonely.com/the-great-chicago-fire-1871/. Accessed 3 Dec. 2024.

History.com Editors. "Chicago." History.Com, 28 Apr. 2020, www.history.com/topics/us-states/chicago. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

"Chicago Police Department History." Chicago Police Department, www.chicagopolice.org/about/history/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

Crawford, Amy. "Outlaw Hunters." Smithsonian Magazine, 31 Aug. 2007, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/outlaw-hunters-163405565/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

"Early Chicago, 1833–1871." The Office of the Illinois Secretary of State, www.ilsos.gov/departments/archives/teaching_packages/early_chicago/doc23.html. Accessed 11 Nov. 2024.

"History Spotlight: Postal Inspector Allan Pinkerton." United States Postal Inspection Service, 2023, www.uspis.gov/history-spotlight-2023/allan-pinkerton. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.

“Life in Chicago in the 1850s.” Classic Chicago Magazine, Chicago. www.classicchicagomagazine.com/life-in-chicago-in-the-1850s/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024

Pinkerton Employee Handbooks, Pinkerton Archives, Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division

"Thieves and Burglars!; Pinkerton's Police, Broadside, 1871." The Great Chicago Fire and the Web of Memory, https://greatchicagofire.org/item/ichi-37933/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

"The Scotch Is Chicago." Scottish American Journal, New York, 1 Sept. 1875.