Pinkerton Racing Services

It was about 1880 that Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, on behalf of the larger horse racing associations, undertook the protection of their racetracks in the United States and Canada against the operation of professional thieves, pickpockets, touts, hoodlums, and bunco louts.

The exploits of “The Eye” — the Pinkerton brothers Robert and William — and their legion of Pinkerton Racing Services agents had become legend. They were often described as standing casually around the tracks, spotting criminals from all over the world and arresting or ejecting them with little trouble. They had the amazing ability, inherent or acquired through years of training, to remember faces and had been known to unsettle the ordinarily steady nerves of those looking for a quick payout, sometimes even driving them to leap the fences to get away from the peering “Eye.”

It became a huge undertaking for swindlers to operate at Pinkerton-protected tracks, but every year, some would test the Pinkerton’s mastery, especially after “Bob” and “Billy” passed Agency leadership to their heirs. It was said that every professional thief knew if they committed a crime at the races that they would never be safe again and they would be pursued to the end.

At the Hambletonian Stakes held at Goshen, NY, in August 1937, Pinkerton agents arrested 30 known pickpockets and racetrack touts. A year later at the same meet, agents arrested 18 pickpockets. In 1949, the Pinkertons ejected or arrested some 950 crooks and other disorderly persons from all the New York racetracks, with a 100% conviction rate.

On the forefront of security innovation: employee identification cards

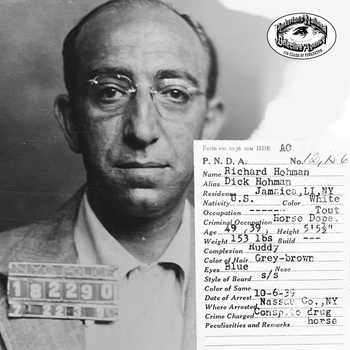

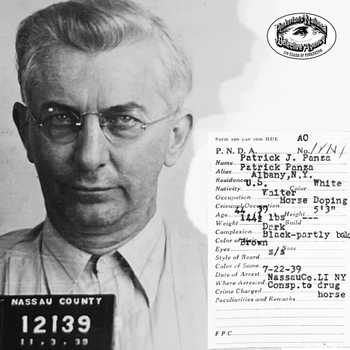

Where there was money, there was crime, even in the King’s sport. The Pinkerton’s watchful “Eye” had all but eradicated crime among horse racing spectators, however, a larger underhanded plot was playing out behind the scenes. Dishonesty on the part of horse owners, trainers, and jockeys was defeating the efforts to maintain a high standard of sportsmanship and safety. The variety of devices and practices available, even in the late 19th century, required the utmost vigilance. It also required sweeping action, and an identification system was needed.

Always on the forefront of security innovations, the Pinkertons, in association with the Jockey Club and racing associations, developed a system of description and photographic identification as a record of all track employees and stable personnel, who were required to carry identification cards. In addition to track security, the system enabled racing associations to bar those who had been involved in fraudulent practices.

Sponging, doping, and ringing lead to new horse identification system

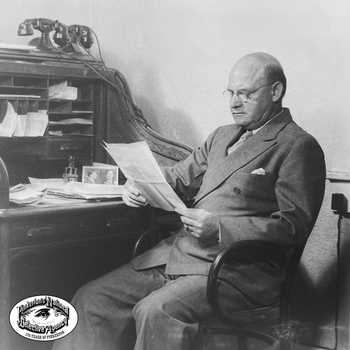

Horse racing has always been big business. R.A. Pinkerton II, great grandson of Allan Pinkerton and the president of the Agency from 1930 to 1965, said that there never will exist any sport widely patronized by the paying public that will not attract crime. That was certainly true at the races.

Horse owners, trainers, and jockeys bent on skullduggery knew no bounds and employed practices that ran the gamut from age-old bribery and extortion to sponging, stimulating, doping, and ringing — the practice of illegally substituting experienced and faster horses for ones with similar looks whose past performances were not as favorable, usually to take advantage of long betting odds.

Ringing passed from an occasional single case at the end of the 19th century to an organized commercial enterprise in the 1920s and 1930s, extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

Racehorses were always required to register with the Jockey Club; however, identification records were not always readily available or accurate. This opened the doors for fraud. Resourceful swindlers would call on former owners or trainers in attendance or paddock judges and clockers familiar with a horse to make an identification before post time without always paying attention to details. In time, it became obvious that a superior horse identification system was needed.

Pinkerton’s, in conjunction with the Jockey Club and the New York Racing Commission, embarked on a painstaking study of the subject and developed a system along the lines of the Pinkerton Rogues Gallery. The system was based upon a minute examination of each horse entered in every race.

All physical features were accurately reported, and although rare until the 1930s, skilled photographers took photos of the horses from every angle to display coloration and marks. No horse arrived at the post without the judges and track stewards positively identifying the horse. By the 1940s, Pinkerton’s Horse Identification Bureau files had some 33,000 thoroughbreds registered.

According to Pinkerton archives, ringing had been virtually eliminated on the major tracks by the late 1930s, leaving in its wake some of Pinkerton’s most spectacular cases detailing international man hunts, clever con men, and ingenious detectives. But those are stories for another time.