This blog is a part of our Scouts and Spies series. Our founder, Allan Pinkerton, and his team of Secret Service Scouts and Spies played a critical role in gathering intelligence during the U.S. Civil War, providing a tactical advantage on the battlefield. Skilled in reconnaissance and surveillance, they navigated enemy territory, monitored enemy movements, and gathered crucial information that aided military decision-making.

Gathering information about the enemy's strength and position was a daunting task for the North’s Union military leaders during the U.S. Civil War in the 1860s. The Southern population was largely united and devoted to their cause, making it difficult to find reliable sources of information. Typically, only Confederate deserters or civilians seeking refuge in the North would provide information, but their reports were often unreliable. The North needed to find a way to obtain more consistent information. As a result, a new intelligence regiment was formed — the Secret Service.

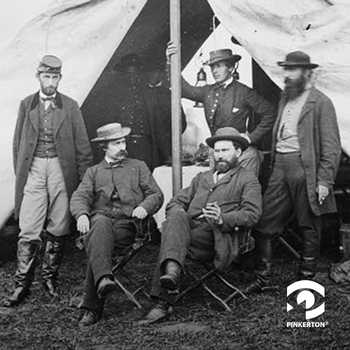

President Abraham Lincoln appointed renowned detective and founder of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, Allan Pinkerton Chief of the Secret Service — sometimes called the Federal Secret Service, Union Secret Service, or Pinkerton’s Secret Service — to establish and oversee intelligence operations. Pinkerton then organized the first Secret Service Division of the United States under General George B. McClellan, then Commander of the Army of the Potomac, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio.

I resolved to at once send some scouts into the disaffected region lying south of us…

“The general informed me that he would like observations made within the rebel lines, and I resolved to at once send some scouts into the disaffected region lying south of us, for the purpose of obtaining information concerning the numbers, equipment, movements, and intentions of the enemy, as well as to ascertain the general feeling of the Southern people in regard to the war,” wrote Pinkerton, who went by the nom de guerre Major E.J. Allen, (Pinkerton, Spy of the Rebellion, 1886).

While handling its military duties through the War Department, the Secret Service also supported the field Armies, State Department, White House, District of Columbia, and other Federal Government departments — it was only post-war that the Federal Bureau of Secret Service was established by Congress. Meanwhile, Pinkerton's Secret Service, with its headquarters in Washington D.C. and agents in the Army of the Potomac, catered to all Federal Departments' secret service needs.

“I fully realized the delicacy of this business, and the necessity of conducting it with the greatest care, caution, and secrecy. None but good, true, reliable men could be detailed for such service, and knowing this, I made my selections accordingly,” Pinkerton wrote.

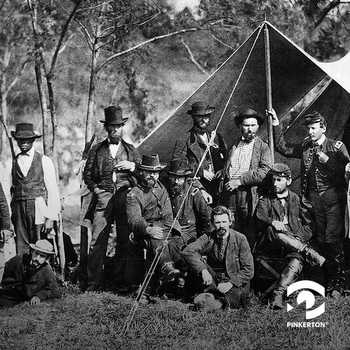

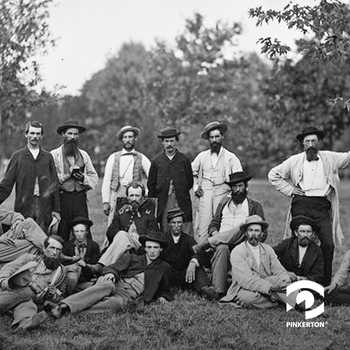

Under Pinkerton's leadership, the Secret Service Department focused on gathering vital information about the Confederate forces, their strength, positions, and intentions. He employed a network of skilled scouts and spies — some of whom were chosen from among Pinkerton’s most loyal and talented detectives.

Decoding military terminology: differentiating spies from scouts

Distinguishing between secret service "spies" and "scouts" proves challenging. The two terms were frequently used interchangeably. In military accounts, a vast majority of individuals labeled as spies would be classified as scouts by military personnel. For them, a spy typically referred to someone permanently positioned within enemy territory, tasked with gathering valuable intelligence for their military leader. Communication with spies was sometimes facilitated through scouts who served as messengers, while the actual spies rarely left their posts.

Scouts also operated under the guidance of a military officer or chief, performing diverse duties such as carrying coded messages, identifying enemy positions, and collecting detailed information about buildings, towns, routes, bridges, and river crossings to aid military movements. The overlap in duties created confusion, further complicated by the tendency to refer to apprehended scouts as spies.

Whether spy or scout, when apprehended, both were hanged for treason.

The eyes and ears behind enemy lines

Scouts were the real eyes and ears of the army and kept in “incessant action,” (The Photographic History of the Civil War, pp. 4). These keen-witted detectives and calvary men were true adventurers, with sharp eyesight and undaunted courage — deployed singly and in pairs, operating covertly, often assuming false identities, and venturing into enemy territory to gather firsthand information about the enemy's movements and fortifications.

Pinkerton’s Secret Service department employed various techniques to gather intelligence, including the interception and decoding of Confederate messages, conducting surveillance, and analyzing captured documents.

During the campaign near Fredericksburg, scouts were equipped with an innovative tool. Each scout carried a pass issued by the commanding general, ingeniously written with a special chemical that remained invisible until exposed to sunlight. The reverse side of the pass contained inconsequential information, devised to mislead the enemy in case of capture. And if captured, the scout could discreetly drop the pass, making it seem like an accidental loss to avoid suspicion — these same scouts would commonly pose as foragers among their own ranks, frequently transporting vegetables, poultry, and other similar provisions to safeguard their anonymity.

If a scout accomplished their mission, a moment of heat exposure rendered the pass visible again, granting them safe re-entry into Union lines and swift access to headquarters where they delivered invaluable intelligence.

When more advanced intelligence was needed, scouts became spies and successfully navigated the hostile environment, contributing significantly to the Union's capabilities. While so many of their names are not widely known, their efforts underscored the importance of intelligence in shaping the outcomes of the Civil War.

Notable Pinkerton Scouts and spies

Buried deep in a folder in the Pinkerton archives housed at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C., there is a newspaper article about the life and times of Civil War secret service scout, Samuel M. Bridgeman. Handwritten in the margin of the 100-year-old newsprint were the names of a few of his colleagues: Timothy Webster, George H. Bangs, William H. Scott, Paul H. Dennis, John Kinsello, John Scully, Pryce Lewis, Harry Knipe, Walter Angle, John C. Babcock.

The handwriting fades, but if one were to look closely, they might also see the names of the other Pinkerton scouts and spies.

Integrity, vigilance, and excellence

In an era marked by uncertainty and conflict, Pinkerton's Secret Service stood as a beacon of ingenuity and bravery. Whether scout or spy, these men and women were integral to the Union’s intelligence operations, venturing behind enemy lines, adopting false identities, and exposing themselves to grave risks. Their innovative methods of gathering intelligence — ranging from decoding intercepted messages to utilizing chemical passes — played a crucial role in the North's warfare strategy. Notable figures, who names were spoken in both whispers and shouts from allies and adversaries alike, displayed unwavering dedication and left an indelible mark on American history and embodied Pinkerton’s values of integrity, vigilance, and excellence.

Pinkerton “scouts” still play a crucial role. Organizations today rely on our research and intelligence to help shape their strategies, identify vulnerabilities, and anticipate threats, ensuring the success and safety of their operations across diverse environments. Trust in the Pinkerton legacy, and let our scouts guide your due diligence process today.

Sources:

Miller, Francis Trevelyan, and Lanier, Robert S. (Robert Sampson) (1911), The Photographic History of the Civil War, New York: Review of Reviews Co.

Pinkerton, Allan (1886) The Spy of the Rebellion: Being a True History of the Spy System of the United States Army During the Late Rebellion Revealing Many Secrets of the War Hitherto Not Made Public, G.W. Carleton.

Pinkerton, Robert, and Pinkerton, William (1905) Timothy Webster: Spy of the Rebellion, Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, Chicago and New York.

The Chicago Times, “Samuel M. Bridgeman: Had an Eventful Life,” December 20, 1894.