Since the beginning of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, Allan Pinkerton, the Agency’s founder, was a stalwart ally to banks and banking institutions, tracking down burglars, sneak thieves, counterfeiters, forgers, and the oft-feared masked hold-up robbers. Ever justice-minded, Pinkerton’s goal was to pursue justice and decrease crime – this was, of course, after he realized that he had a natural talent for investigations. He had discovered, unintentionally, currency counterfeiters near his home in Dundee, Illinois. And over the next few years, Pinkerton gained significant fame solving a series of counterfeiting cases, which ultimately led to the formal establishment of his detective agency in Chicago.

A few years later — when Chicago was booming, its population and crime outpaced official law enforcement — Pinkerton formed the Pinkerton Preventive Patrol (PPP), the first uniformed police patrol and private security firm in Chicago. All the banks in the city were under its watch. As the Agency expanded across the country, so did the PPP.

The thief and burglar are ever on the alert to discover the weak points in the bank buildings that come under their notice, and it behooves everyone to see that no such weakness exists. Watchmen upon the inside and outside of the building, strict discipline among the clerical force, and a careful watchfulness, maintained upon all strangers who approach the bank, or are seen in the vicinity, will tend very much to secure the protection so much needed. ‘Eternal vigilance is the price of safety,’ and this fact is in no case more true and potent than in guarding banking institutions from the attacks and depredations of the daring and skilled burglars who exist in such large numbers throughout the country. –Allan Pinkerton, Thirty Years a Detective.

The Heist That Started It All: Bank Robbery 101

In the wake of the Civil War, the United States witnessed a new wave of audacious crimes — armed daytime bank robbery. Until the mid-1860s, crime against banks consisted of nighttime burglaries, sneak thefts, forgeries, counterfeits, and other schemes that were conducted in a shroud of mystery — crimes which Allan Pinkerton and his Agency investigated and solved aplenty. But now, outlaws were becoming increasingly daring, emboldened by the turmoil of post-war America. They became what was known as “hold-up robbers.”

And they didn’t just focus on banks. These gangs menaced trains, express cars, and stagecoaches. And in each instance, the tales were harrowing. According to Pinkerton’s archives, the gangs held-up banks in the daytime, robbed trains at night, murdered respectable citizens who resisted them, and killed officers who attempted their arrest.

William Pinkerton, son of the Agency’s founder, said that they found that many of the early hold-up robbers were “dare-devils” of the Civil War. “Those from the Southwest who engage in guerrilla warfare, where, as the pride of the State which sent them to the front, and, because of their ambuscades, raids, and lawless acts during the war, they were received as heroes when they returned to their homes. The James boys, the Youngers, the Renos, the Farringtons, the war giving them the reckless life they longed for and experience fitting them for the life of crime they inaugurated immediately after…There is no crime in America so hazardous as hold-up robbery.”

Historians often cite the Clay County Savings Association, Liberty, Missouri, on February 13, 1866, as the location of the nation's first armed daytime bank robbery, allegedly committed by associates of the notorious James-Younger gang. The robbers eluded capture and were never positively identified. This was just the beginning of a 10-year crime spree by the James-Younger gang that included more than 11 banks, several railroads, stagecoaches, and county treasury offices where a quick score could be had. In 1876, the James-Younger gang met their demise, with most of the members wounded, killed, or captured. Those that remained regrouped under the name the James Gang and continued their criminal ways until the death of Jesse James in 1882. There is nothing in our archives that indicates we were part of the Clay County Savings Association investigation, although over the ensuing years, Pinkerton’s operatives would cross paths with these gangs.

One of the earliest bank robberies investigated by Pinkerton's took place at Mylart's Bank, Scranton, Pennsylvania that same year. Very little information is available other than that Pinkerton’s operatives moved in quickly. Two men were arrested and convicted, and the stolen money was recovered — $50,000.

Also in that same year, another heist took place, this time at the National Village Bank of Bowdoinham, Maine, on June 22. Early in the morning, before official banking hours, a group of seasoned and armed criminals forcefully entered the home of the bank's cashier. Under the threat of violence against his family, the cashier turned over his keys. He was forced to accompany the desperadoes to the bank where they stole approximately $80,000. With money in hand, they took the cashier home and fled, leaving him and his family tied up. The Agency, summoned by the beleaguered banker once he was freed, collaborated with law enforcement agencies from Maine to New York to successfully identify, capture, and convict the robbers.

Coal Miners and Criminals: The Carbondale Bank Caper

The Carbondale bank robbery, orchestrated by members of the notorious organized crime ring in the coal regions of Pennsylvania called the “Mollie Maguires,” was a defining moment in the history of early bank robberies and highlighted Pinkerton's crucial role in capturing high-profile criminals.

On January 14, 1875, the First National Bank of Carbondale became the scene of a brazen daylight robbery when the robbers seized the opportunity to overpower the sole cashier during the lunch hour. This audacious crime not only involved the theft of $24,000 but also drew significant attention from financial institutions nationwide, creating an imperative for their capture.

William Pinkerton’s brother, Robert Pinkerton, personally took charge of the investigation. By 1875, he had already gained a reputation for relentless pursuit and strategic expertise. Assisted by a half dozen or more of Pinkerton’s “keanest, cleverest, and most cool-headed operatives,” Robert established his headquarters in Lackawanna County and conducted nightly trips to Carbondale. For a time, the bank robbery baffled the veteran sleuths, and more than one of their number returned to New York broken in health as the result of their night vigils. They were replaced by other operatives, and the quest was continued. After a few weeks, Pinkerton and his team prevailed. The gang was captured and confessed, telling a tale of wandering “swag,” hidden at various places at various times.

What makes this case particularly remarkable is that it highlighted Pinkerton's innovation in detective work and long-lasting impact on law enforcement practices, as well as foreshadowed further investigations into the "Mollie Maguires," which would eventually contribute to dismantling the organization.

Luck, Training, and a Little Sleight of Hand

Historians noted that during the years between the close of the war and the time of Allan Pinkerton's death 1884, there was hardly a criminal case of any importance in the United States in which Pinkerton was not engaged or consulted.

“For banks,” wrote Allan Pinkerton, “I make respective specialties of investigating the habits and honesty of employees, swindling of creditors, searching for and collecting evidence, both in civil and criminal cases, of testing the reliability and character of witnesses, serving papers, and investigating patent infringements.”

Of course, in Allan’s words, the work with banks sounded much more mundane than modern thrill-a-minute heist movies. Regardless, the Agency’s dance card was always full, and no case was too small in the pursuit of justice. What set Pinkerton’s apart from others emerging in the field was the training of the operatives…and luck.

“You are always learning something in a new game you play with men,” stated William Pinkerton. “We train our own men. We’d rather begin with them and teach them spotting, shadowing, and roping. Luck’s been with us a great deal, and luck is everything in this business. Luck and training make a good detective. Training more than heredity.” (King of the Sleuths: A Study of the Modern Detective, Alice Rix, The Call, San Francisco, October 23, 1898.)

Pinkerton’s operatives were renowned for their expert investigative skills and meticulous attention to detail. They often studied Pinkerton’s Rogues' Gallery, enabling them to swiftly recognize and identify criminals on sight. This dedicated practice ensured that, when out in the field, they could effortlessly spot and identify criminals.

While on his way home one night from Pinkerton’s Chicago headquarters in the summer of 1870, William Pinkerton, noticed known thieves Walter Sheridan, Charlie Hicks, and Phillip “Baltimore Philly” Pierson riding together on a streetcar. Intrigued, he followed them to the Chicago and Alton Railroad Station, where he saw them purchase tickets for Springfield, Illinois. The following day, the First National Bank of Springfield was robbed of $32,000.

And while some of the cases were solved in just a few days — notably the La Liberty Gang payroll heist — most took weeks to months solve. The Agency was always in for the long game.

Partnering with the American Banking Association

By 1894, bank crime was increasing. Banks were losing hundreds of thousands of dollars to professional forgers, swindlers, sneak thieves, and hold-ups every year. Because of extensive losses to banks, Pinkerton’s established a pivotal partnership with the American Bankers Association (ABA), nearly doubling ABA membership to more than 3,300 banks nationwide in the first four years of the partnership. By 1909, there were 11,000 ABA members. Banks flocked to the protection of the organization and the Pinkerton’s.

The Houston Post published the story of two bank robbers who returned $50,000 in negotiable bonds they stole when they found out (after the fact) that this particular bank was protected by Pinkerton’s. The robbers addressed a note to the bank president that read, “Put your ABA signed out where your customers can see it…” (The Pinkerton Story, Horan.)

By the early 20th century, bank robbery was practically a lost art in the United States, said William Pinkerton in a keynote speech to the International Association Chiefs of Police in 1907. “Bank vaults are never blown open or even tackled by burglars except…in isolated country places, as a rule. The perfection of protection appliance in the vaults of city banks has rendered breaking into them practically an improbability.”

In the speech, he detailed the demise of the last train and bank robbery gangs, notably the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang — a loose association of outlaws who used a remote hideout called the Hole-in-the-Wall, located in the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, as a safe haven. This hideout was used by various outlaw gangs over the years, including the Wild Bunch, led by notable figures such as Robert Le Roy Parker, alias George Parker, better known as “Butch Cassidy,” and Harry Longbaugh, alias “The Sundance Kid.” At that time, all the gang members were either deceased or in prison. Only Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, along with Longbaugh’s lady friend, Etta Place, evaded capture. They had fled to South America, and we all know how their stories ended.

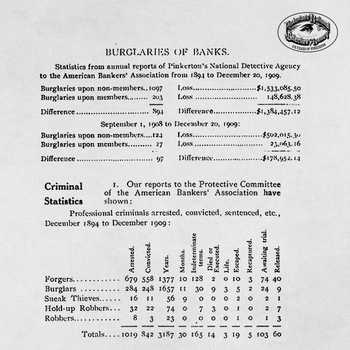

Rogues Galleries and a Who’s Who of Master Forgers

In the years leading to the ABA partnership, forgery had become prolific and brazen. Banks were defrauded by organized crews of professional forgers who took advantage of the time it took for the depository bank to verify and receive funds from the issuing bank. This process could take up to a month, by which time the crew withdrew their funds and moved on. During the 15-year ABA partnership, Pinkerton was instrumental in breaking up and convicting all but one of 73 crews of forgers and check swindlers, comprising over 200 operators. There were individuals at work, too. In total 679 forgers were arrested, and 558 were convicted.

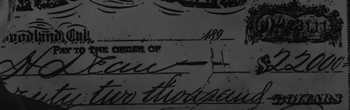

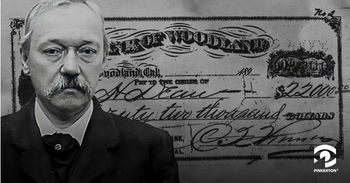

Pinkerton’s annual reports to the ABA read like a who’s who of forgers. Among them was one of the most famous and talented forgers of his time, Charles Becker — also known as “The Dutchman” and “The Prince of Forgers” and other aliases. Becker had few equals and no peers in his criminal career. According to William Pinkerton, Becker was nearly invincible to arrest because he was simply that talented. It required the most extraordinary skill from Pinkerton’s in collaboration with the ABA to track down Becker and his crew after his most famous heist. Becker raised a perforated $12 draft from the Bank of Woodland to $22,000. A member of his crew deposited the draft at the Nevada National Bank, San Francisco, California, in December 1895. The next day, Becker and his accomplices withdrew $22,000 in gold and disappeared. Pinkerton’s caught up with Becker and his crew a few months later and helped to secure his arrest and conviction in one of the most hotly contested trials of the time.

It should also be noted that although many crews still operated throughout the country, by 1901, no sneak thieves operated on ABA Banks.

Protection and Perseverance: The Pinkerton Bank and Banking Service

At the end of 1909, the ABA and Pinkerton’s parted ways over a dispute regarding, of all things, money. In 1910, Pinkerton’s created the Pinkerton’s Bank and Bankers’ Protection (PBBP) subscriber service. Unlike the ABA, a national trade association that even today promotes the health and welfare of the banking industry, PBBP had but one banking feature: to decrease crime on subscriber banks by burglars, sneak thieves, robbers, forgers, and swindlers. The PBBP did not cover internal matters such as embezzlement or employee theft. Pinkerton’s could, and often did, investigate those matters, but they were a separate scope of work.

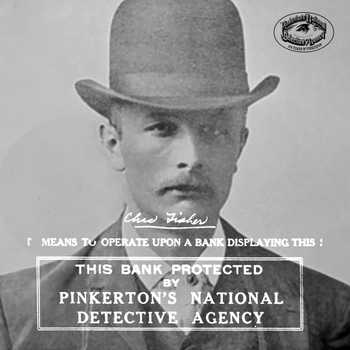

Pinkerton's innovative strategies, such as distributing a tailored rogue’s gallery album of photos and other information on known criminals, significantly reduced bank-targeted crime. Banks that displayed their Pinkerton’s membership signs in their windows, at teller stations, and on their safes and vaults — This Bank Protected by Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency — became practically immune to incidents by sneak thieves and the "old-time" professional safe burglars.

“Loss and annoyance may be prevented, and the arrest of criminals be the result!”—Pinkerton Bank and Banking Protection circular.

And those who dared to prey upon banks soon discovered why Pinkerton’s name was feared. Criminals knew the Agency would use every detective means in its power to discover, apprehend, and secure a conviction of the criminal. And recover the currency, whether cash, gold, silver, or bonds. Pinkerton’s surveillance and shadowing methods were second to none. Insurance companies agreed. National Surety Company offered a 10% discount on forgery and burglary insurance to banks and bankers protected by Pinkerton’s. In the first three months of the PBBP, Pinkerton’s detectives arrested 32 criminals who attacked 45 banks — 36 of which were subscribers.

And a Marketing Moment for the PBBP

On April 29, 1910, Pinkerton’s arrested Charles Fisher, born J.B. Ford — noted forger, mailbox robber, burglar, and bank sneak — in New York City for attempted forgery. Fisher had just been released early from a 10-year sentence, and after his arrest, he was sent back to prison to serve a two-and-a-half-year term.

This was not the first time Pinkerton’s arrested Fisher, but it was the last. Make no mistake, it would not be the last time Fisher would be arrested, just the last time Pinkerton’s was involved. Oft compared to Charles Becker, Fisher was considered among the cleverest in his craft. He was also regarded as one of the most notorious and dangerous forgers in the United States during his time.

By his own admission, Fisher was born a thief. He said he began his career of crime when he was just 12 years old, stealing from his classmates and his grandparents, who found him to be incorrigible.

Pinkerton’s criminal file on Fisher begins in 1874 when he was arrested in New York and served 18 months in the House of Refuge, NYC. He was arrested again on August 9, 1876, and served two and a half years at Blackwell’s Island, NYC. And the list continues.

On December 8, 1897, Fisher was escorted back to the United States by American law enforcement agents and Pinkerton’s operatives, who located Fisher in prison in London, serving out a six-month sentence for some small fraud in that country. (Fisher and his gang had fled to Europe after a daring jailbreak on November 10, 1895.) Pinkerton’s operatives were taking Fisher to Cincinnati, Ohio, to finally stand trial for forgery committed on an ABA bank in 1894. When he was caught, he did not resist extradition; instead, he stated, "I would much rather be hanged in America than in England any day.”

Among his effects at the time of his arrest in 1910 were 1,985 checks and drafts on banks in 10 states, which had been secured by theft and fraud from lithographing firms in New York City. Pinkerton used this case to market the PBBP service. They distributed a bulletin urging bank officials to caution their lithographers not to give out sample checks or drafts to any person, unless upon written authority from the bank. They further warned:

Sample checks should have the word "SAMPLE" printed prominently on its face and be perforated with the word "VOID." Surplus checks should always be kept securely under lock and key. Bank officers and employees are urgently requested to carefully read the confidential warnings issued to subscribers to PINKERTON'S BANK AND BANKERS' PROTECTION; loss and annoyance may be prevented, and the arrest of criminals may be the result. Should any person present a doubtful check or draft, detain him, under the pretext of verifying the signature, and consult the cashier, or telephone the maker. Should it prove to be a forgery or bogus, arrest the presenter and surrender to your local police. –PBBS bulletin

An interesting note about Fisher: He waxed poetic about penitence and “confining his footsteps” during his imprisonments. His good resolutions were always, however, short-lived. Until the time of his final arrest in 1920 at 72 years old, Fisher had spent an aggregate of 30 years in prison in the United States and other countries.

The Roaring 20s: Detectives, Protection and Armed Escorts

The Agency expanded their bank protection to include executive, onsite, and asset protection. In other words, personnel protection for bank officials, guard postings at bank buildings, and armed escorts for transport vehicles — especially for armored trucks when they emerged on the scene in the late 1920s. Not all banks, however, found the need for Pinkerton’s to ride ‘shotgun’ in their armored trucks (like we did on the Wild West stagecoaches). Criminals found these trucks and payroll deliveries to be especially lucrative targets.

In 1929 New Orleans, Pinkerton’s Superintendent G.L. Stancliff noted banditry was rampant. Hardly a day passed that a heist or robbery hadn’t taken place.

On one particular Friday morning, the day before the end of the month, Hibernia Bank and Trust’s money truck was robbed by five masked individuals, suspected as the Red Kelly Gang. Knowing the exact streets it would travel, the masked men waited at a predetermined intersection. As the truck arrived, the bandits blocked its path with a stolen car. Three of the gang, armed with sawed-off shotguns, forced the driver to continue driving to a sparsely populated area, where they incapacitated the truck driver and guards, abandoned them, and took off with the truck and $104,000.00. Later, the money truck was found set ablaze at the city's edge.

Three months later, and no closer to recovering the stolen money, the bank, in conjunction with two insurance companies, contacted the Agency. A secret operative was embedded at the suspected gang’s headquarters — a complex with apartments, a mechanic’s garage, and a silent bar, or speakeasy. It didn’t take long before he had positively identified the Red Kelly Gang as the culprits. Pinkerton’s then collaborated with local law enforcement to gather evidence and arrest the culprits. All but one of the gang members, who became a criminal informant and turned on his associates, received long prison sentences.

Stakes, Stocks, and Security

By the 1960s, Pinkerton’s continued to solidify its position as a formidable protector of banking institutions. A noteworthy demonstration was the transfer of stocks and bonds from the old Chase Manhattan building to the newly constructed Chase Manhattan building undetected through the streets of Manhattan, a move that underscored the Agency’s unmatched expertise in securing high-value assets during complex, high-stakes operations.

This era was not just about physical security, but also about adapting to the ever-shifting challenges in financial protection, further cementing Pinkerton's storied reputation. Pinkerton's strategies and innovations have evolved continuously, maintaining robust partnerships with banks worldwide, a testament to its unwavering commitment to security.

Today, Pinkerton stands as a global leader in the financial security sector, offering cutting-edge solutions that cater to the modern needs of banks and financial institutions, while also respecting the legacy of vigilance and dedication established in 1850.