In July 1896, John “Charles” Becker and his accomplice, James Creegan, were convicted in San Francisco, California, after one of the most hotly contested trials of its time. The defendants had engaged good counsel — presumably using monies gained from their forgeries — who made a good case. It required the most extraordinary skill from Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency, the American Bankers Association, and San Francisco police detectives and prosecutors to amass the evidence. According to newspaper reports, it was the knowledge of Becker’s unrivaled methods and appreciation of his character, more than any single thing, that won the day.

When speaking about the Charles Becker gang, William Pinkerton, head of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency Western Division and son of the Agency founder Allan Pinkerton, stated, “The leaders of which were practically immune from arrest because of the insufficiency of the evidence necessary to convict.”

William’s brother, Robert A. Pinkerton, head of the Agency’s Eastern Division stated, “There never was any personal feeling between Charley Becker and ourselves. He never did anything against us. It was purely a matter of business.”

The Elusive Career of Charles Becker

Charles Becker — known as “The Dutchman” and “The Prince of Forger” among other aliases — had few equals and no peers in his criminal career.

Becker was a papermaker, lithographer, engraver, and etcher by trade. He was also an expert in inks and their eradication with acids. His remarkable skills and expertise in engraving plates, altering negotiable paper, and executing forgeries made him highly sought-after and valued by prominent counterfeit securities operators and bank swindlers worldwide. He was one of the few men of his time who could refill perforations. The finish on many drafts and checks prepared by Becker, using camel hairbrushes, was so meticulous that they eluded detection even under a microscope.

Throughout his criminal career, Becker remained elusive, often changing identities and evading capture. His extensive network of criminal associates allowed him to operate across borders, making it difficult for law enforcement to track his movements.

Despite the lack of effective international extradition treaties and the legal limitations of statutes during Becker's criminal activities, the Pinkertons pursued Becker and his criminal associates with customary relentlessness. While unable to bring him back to America from Europe, where he was repeatedly located by Pinkerton operatives, the Agency collaborated with Scotland Yard and European police forces to thwart the gang’s criminal endeavors.

Charles Becker’s Last Great Scheme

Although Becker had previously served time for forgery and bank robbery in both the United States and Europe and made the international news scene — including a story about his daring prison break in Smyrna, Turkey — it was his last great forgery that captured the nation’s attention.

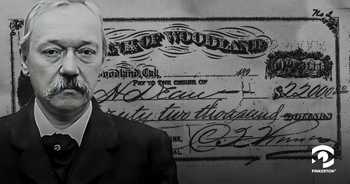

The notorious Becker and Creegan were charged with altering a perforated $12 draft from the Bank of Woodland. Becker refilled the perforations and changed the amount to $22,000, which was deposited on December 18, 1895, at the Nevada National Bank, San Francisco, California. The next day, Becker and his gang withdrew $22,000 in gold and disappeared.

The forgery was discovered at the end of the month when the Woodland Bank received its returns.

The American Bankers Association promptly notified the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, who suspected it was the work of the Charles Becker Gang, consisting of Becker, the forger; James Creegan, the middleman; Frank L. Seaver, alias A. H. Dean, presenter; and Joseph McClusky.

It took just a few weeks to locate the gang in St. Paul, Minnesota, where the gang already had plans in motion to swindle two banks — Seaver identified the banks and opened accounts. Seaver and McClusky were arrested in that city and then taken back to San Francisco to face charges.

Unfortunately, there was insufficient evidence to hold McClusky, and he was released. As for Seaver, there was more than enough evidence and witnesses to convict him. Once he realized that his gang was not going to honor their pact of providing legal aid for him, he made a full confession implicating Becker as the forger and Creegan as the middleman. This provided the evidence they needed for a Grand Jury indictment.

Shadowing Becker and Creegan Across America

After Seaver and McClusky’s arrest, Becker and Creegan fled St. Paul, closely pursued by three of Pinkerton’s finest shadows, Operatives Fallon, Lardell, and Minster. Becker headed to his home in Brooklyn, New York, and Creegan went to Newark, New Jersey. The Pinkertons kept both men under constant surveillance, while they awaited an indictment from San Francisco.

In April 1896, the Pinkerton operatives learned from informants that Becker and Creegan arranged to leave the country for Guatemala via Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. To frustrate their plans and keep them in the country, the operatives shadowed Becker and Creegan to Philadelphia and arranged for their arrest, even though they could not be held for the San Francisco crime, yet. The Philly police were able to detain the pair just long enough for the steamer to set sail without them.

With their escape plan ruined, Becker returned to Brooklyn and Creegan to Newark, each one continuing under the watchful Pinkerton eye.

In May 1896, an indictment was finally returned for the San Francisco job. Operatives patiently waited for Becker and Creegan to meet again, which happened just a few days later. On May 13, 1896, the two met up at the Park Hotel in Newark, where Creegan had been staying.

In what can only be described as a dramatic operation, the Pinkertons arrested Becker and Creegan together outside at the corner of Broad and Market Streets. Becker did not resist, but Creegan put up a fight and made an unsuccessful attempt to escape. When searched, Creegan had $2,345 — one $1,000 bill and the rest $100 bills and smaller — sewn inside his clothes. Upon seeing the bills found on his partner, Becker coolly commented, “There goes the boodle.”

“There can be no doubt,” said William A. Pinkerton that morning, “that in capturing Charles Becker we have secured a man who is by all odds the cleverest forger in the country.”

From Prison to Redemption: Becker's Life After San Quentin

While awaiting a retrial in August 1896 — due to a jury error during the July trial — Creegan confessed to his part in the con. He was sentenced to serve two years in Folsom Prison, CA. Because of Creegan’s confession, Becker also confessed and petitioned the Supreme Court to reduce his life sentence to seven years in San Quentin State Prison, CA, where it is said he devoted his talents to pen sketches and artistic printed visiting-day programs.

After his release in 1903, Becker returned to his home in Brooklyn where he was determined to stay honest — for the most part. He operated a saloon where his friends would often engage him in friendly wagers. During these bets, he would forge his friends' signatures on small drafts and then cash them at their banks.

It was repeatedly alleged that Becker, after his release from San Quentin, received a $500/month annuity or pension paid by the Agency and the American Bankers Association so long as Becker kept out of trouble and did not cause any problem to them. Of course, it was adamantly denied by all parties involved. (It should be noted that it was the secretary to the San Quentin warden who first shared the news of Becker’s pension.)

Becker was, nonetheless, employed as an informant – codename Gardenstone – by Robert A. Pinkerton for Pinkerton’s Racing Services at the New York area racetracks. Robert wrote in a letter to his brother William, “[Becker] states that he has made up his mind to reform and to endeavor for the rest of his days to earn an honest living; and that he proposes to abandon all forgery operations in the future.”

William responded, “I hope that Becker will get up some…scheme that will help to make him honest. I should dislike to prosecute the old man again, but business is business, and I should have no hesitancy in doing so in case he continued in his life of crime.”

Remembering “Charley” Becker

Becker lived the rest of his days peacefully. He died at home of natural causes on September 9, 1916. His obituary read:

Few of the men who…have patronized the racetracks of the metropolitan district have paid more than passing attention to the short, rather pallid, gray-haired and gray-mustached man with pleasant hazel eyes who was to be seen wandering around like a casual visitor rather than a (gambler) wherever the thoroughbreds ran.

Occasionally an old-timer…would mutter, ‘That’s Charley Becker.’ The Pinkerton men, of course, knew who he was. But to the thousands who saw him, there was nothing in his face or manner to tell that his fingers could raise a $12 check to one of $22,000, so skillfully that the latter amount would be handed to the bearer by the paying teller of any bank in the United States without question.