Detectives from the historic Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency were the most renowned in the world, hailed for their remarkable investigative skills and relentless pursuit of justice, often tracking criminals to far reaches of the globe. They underwent rigorous and comprehensive training, including mentorship by a seasoned detective who not only passed along the Agency’s tried and true methods for tracking down criminals but also identified where a new detective might be most successful.

“Shadow detectives,” or covert specialists, were one of the Agency’s detective classifications. Agency leaders said these detectives were among the most difficult to find. While some detectives operated in the open, shadows were adept at not being discovered — shaded, as it were. Once a shadow had proven their ability, they were always assigned to that type of work, “for detectives are multitudinous, but shadows are rare. Shadows are like poets; they are born, not made.”

... shadows are rare. Shadows are like poets; they are born, not made.

A shadow needed to be the least conspicuous person on the street, absolutely commonplace and uninteresting. This most special class of operatives was honored for their ability to always appear to be about their own business, oblivious to the target individual.

According to the Agency’s manual on shadow work, “Shadows must have impeccable judgment, be quick in action, and be able to extricate themselves from all manner of difficulties without betraying their presence.”

Shadows for specific cases

While shadows were highly esteemed, the Agency never undertook shadow work unless the client considered it a necessary investment. In those cases, shadows submitted frequent reports that were closely scrutinized for evidence to continue the shadowing work as circumstances and conditions unfolded.

The Agency’s shadow work was frequently the determining factor between success and failure in operations in which shadowing was a part. Without fail, the Agency deployed shadows specifically to determine a subject’s movements and uncover one or two crucial facts. Careful shadowing would invariably show the absence of a foundation for suspicion or establish facts to the contrary.

Each time a subject is lost should be considered a defeat in our work and treated as seriously as we would treat a failure in another type of work.

Unseen and unsung heroes

Pinkerton’s archived case files would show that most shadows were referred to by their initials, last names, or agency-assigned code names. In some cases, they remained unnamed in the case files and, with few exceptions, unnamed in newspaper articles, leaving little clue to their identities.

This was, of course, “to obviate any possibility of the operative being recognized” so they could continue to “serve the ends of justice; purge society of the degrading influences of crime; and to protect the lives, the property, and the honor of the community at large,” just like Agency founder Allan Pinkerton proclaimed.

The Agency instructed shadows to never talk about their work — most certainly not to the media. Pinkertons who were named in the media were Agency managers and superintendents who were given explicit permission by Agency principals to speak on behalf of the Agency, operatives who were recognized at the scene of the crime by an industrious reporter, or those called to testify in court about a specific case and had to identify themselves.

In one high-profile case, however, the Agency broke protocol and allowed the media to know the gender of two female shadows, who, from all reports, were spectacular at their jobs.

When no one else could find the fugitive bank robber of the First National Bank of Milltown, New Jersey, in December 1920, the Agency deployed two female shadows to the case. In early January 1921, these women found the criminal’s young wife, who was hiding in New York City. They proceeded to shadow her for several days until she unknowingly led them to her husband in Providence, Rhode Island, where he was arrested the moment he embraced her at the train station. The two agents then simply disappeared back into the shadows, unidentified and ready for their next assignment.

Automobile shadowing techniques

At the dawn of the age of the automobile, the Pinkertons wrote the book on automotive shadowing techniques. For example, if a subject moved about in an automobile — driving his own car, being driven by someone else, or using taxicabs — experience proved that it was impractical and unsafe for one operative to drive an automobile, watch traffic and pedestrians crossing the highway, and observe traffic controls while at the same time trying to follow the automobile under shadow. Two shadows were assigned, one to drive the car and one to keep a keen eye on the subject, quickly alighting from the vehicle to shadow on foot when necessary.

The Shadowing Operations Methods manual also included what to do in certain traffic conditions, on residential streets, or if a subject drove erratically, stopped abruptly, or made unexpected turns. If the subject abandoned their automobile, both operatives followed on foot or used whatever other transportation methods the subject used, including trains, streetcars, or taxicabs.

When the subject drives fast, recklessly, or with disregard for traffic lights, etc., it is preferable to drop him and pick him up later rather than run the risk of an accident. “Light crashing” and reckless driving are to be avoided, especially in congested districts and on slippery streets.

How Pinkerton Agency shadows solved a jewelry robbery

In one noted case, the Agency was hired to investigate a jewelry robbery in New Orleans, Louisiana. Diamond jewelry — 599 pieces totaling $122,000 — disappeared from the hotel room of a traveling jewelry salesman. Forced to start the investigation from scratch with no leads, seasoned detectives hit the streets.

After a few hours of interviews, detectives found a small lead. Two off-duty ticket agents at the New Orleans train station stated they sold tickets to a woman and two men just minutes before the 7:25 pm departure of the Illinois Central Railroad train to Chicago and New York the night before. The agents gave a fair description of the trio and their baggage, stating that they all acted in a somewhat nervous and excited manner.

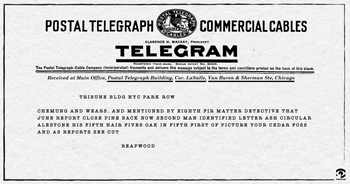

Leaving no lead unexplored, the operatives telegraphed coded messages to the Pinkerton offices in Chicago and New York to set detectives to work and meet the trains at their respective stations.

The train from New Orleans had already arrived and departed Chicago by the time the shadows arrived at the train station. However, the Agency’s New York office sent four of their best shadows to the New York train station. They were waiting at the gates when a woman and two men fitting the ticket agents’ description emerged from the train, but separately.

One detective followed the woman, another the first man, and the other two detectives followed the second man. Eventually, the two suspected men met up at a hotel. They then took taxicabs to several jewelry stores and a pawn store before returning.

At the hotel, the two men met a third man. A few short hours later, this third man attempted to sell the stolen jewels to a pawnbroker in NYC. Traveling by taxicab and then private car, he unknowingly led one of the shadows straight to the stolen jewelry. The operative notified the Agency’s Criminal Investigations Force who, along with New York City police detectives, apprehended the third man and recovered most of the jewelry. More of the jewelry was later recovered from a safe deposit box owned by one of the thieves.

Within the next two days, all three thieves were arrested, thanks to discreet and ever-watchful Pinkerton shadows. Unfortunately, the third man got away because the shadow felt it was more important to stay with the jewelry at the pawn shop instead of following him. It was said that he fled to Europe. When he returned to the United States a few years later, however, the Pinkerton shadows pursued him to his eventual arrest.

Hopwood, an expert shadow

James J. Fallon — codename Hopwood — was one of the most expert shadow detectives in the United States. His successes in shadowing professional criminals invariably identified criminal contacts and revealed evidence of criminal enterprises, the foreknowledge of which enabled protective measures to thwart the criminals. Fallon served the Agency his full career and retired in February 1925 with an enviable record of detective achievements, among which was his apprehension of noted forger Charles Becker — known as both “The Dutchman” and “The Prince of Thieves” — the most dangerous and most sought-after forger in the country, able to perform the cleverest work known to bank swindlers.

Sources:

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "125 East 42nd Street - Lexington Avenue" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1887 - 1964. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-c33d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "125 East 42nd Street - Lexington Avenue" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1887 - 1964. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-c33c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99