There was an air of mystery about everything at the old Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Pinkertons forged their reputations by keeping confidences and solving mysteries. Dedicated to the mission, the Agency’s founder, Allan Pinkerton, assigned code names to not only operatives but also to informers whose identities needed to be protected for covert correspondence and reference.

Woods: the good guys

In the Agency’s post-American Civil War years, the good guys — or “woods” because their code names uniformly ended with “wood” — made good use of the newly completed transcontinental telegraph, signed by code names when secrecy was essential, thwarting the efforts of competitors and spies who attempted to intercept the messages and messengers. The secrecy of the code names that Pinkerton insisted upon was maintained through the fourth generation when Robert A. Pinkerton II, or Lowood, the last Pinkerton to oversee the Agency, resigned his position as President in 1965.

Today, the Agency no longer uses code names for covert activity, but keen-eyed visitors to Pinkerton’s headquarters may notice that each office has been assigned a fitting historic code name, unique to the occupants and their jobs.

Ciphers and codes

Secret codes and ciphers have long been associated with secret agents who operate from behind the spyglass, like Pinkerton operatives who were masterful at going undetected. For nearly a century, from the beginning of the U.S. Civil War in 1861 to the late 1950s, these Pinkertons often used coded messages when sending telegraphs.

Agency founder, Allan Pinkerton, learned how to code messages — using a relatively simple military cipher designed for the battlefield — when he served as the head of the Union Secret Service in the Civil War. After the war, Pinkerton refined the cipher and assigned code names to the Agency’s operatives, executives, allies, and informers. That practice continued with his successors, his sons and grandson, Robert Pinkerton, William Pinkerton, Allan Pinkerton II, and Robert A. Pinkerton II.

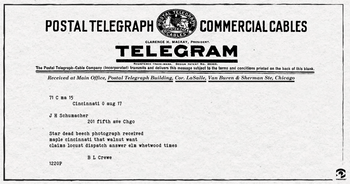

One such telegram was sent on August 17, 1907, regarding urgent Agency business and breaking news. While news in 1907 didn’t spread at the rate of nanoseconds, the media was quick to pick up on the stories they thought people might want to know, like the death of one of the greatest detectives of the time, Robert Pinkerton Sr., code name Whetwood.

Only a few people at the world-famous Pinkerton National Detective Agency had even heard the news by the time the Cincinnati Times-Star received a wire dispatch from overseas.

Per Agency protocol to run all media inquiries through the main offices in either Chicago or New York, Cincinnati Office Manager B. L. Crowe sent a telegram to Chicago Superintendent Joseph Schumacher.

“Star dead beech photograph received maple cincinnati that walnut want claims locust dispatch answer elm whetwood times”

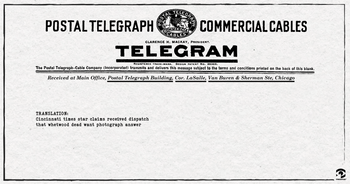

Translation: “Cincinnati times star claims received dispatch that whetwood dead want photograph answer”

Schumacher’s uncoded reply read simply, “Report correct. Furnish photo if you have one.”

Stones: Pinkerton’s infamous criminal informants

Agency operatives occasionally secured information from informants whose identities needed to be protected. The Agency had a long and enviable list of informants, including those who had a criminal record or were accepted in the criminal underworld. These criminal informants — known inside the Agency as “stones” because they were assigned code names that uniformly ended with “stone” — were a who’s who of forgers, pickpockets, sneak thieves, confidence men, bank burglars, safecrackers, disorderly saloon and pool room keepers, bookmakers, cardsharps, and the like.

The only evidence of the stones — with code names such as Deafstone, Allstone, and Sarfstone — was scrupulously noted in secret cipher journals in the New York and Chicago offices that could only be accessed by high-ranking Agency officials. Once code names were assigned, Agency communication referred to the informants almost exclusively by their stone names, and typed letters were often hand-inked with the words, “Do Not Decipher.”

The identities were kept so confidential that even the informants themselves never knew of the other stones. In 1899, Agency principal William Pinkerton wrote a letter to the New York office superintendent, George H. Bangs, about information he personally received from Doublestone, detailing the activities of a couple of his associates, also pickpockets and sneaks, whom Doublestone named but whom Pinkerton referred to only as Cimstone and Kidstone. The information was later corroborated by Cobblestone.