The 1900 U.S. Tour of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders of the World was a spectacle to behold, at least according to the local newspapers across the country. Spectators by the thousands flocked to the cities where the show made an appearance — one newspaper even stated that over the course of one summer, some 30,000 people arrived in their town to see the traveling shows that

made an appearance — there were three in that town, including the Ringling Bros circus.

It was the magic age of the traveling show where showgoers were treated to a roaring good time, the likes of which they had only heard about from the country’s Wild West days — sharp shooters, fast horses, stories, and tricks, and pickpockets and sure thing gamblers, con men, and scalpers, although back then they were called ticket speculators and they almost got away with it too, if it wasn’t for Pinkerton Detective William Minster who was embedded in the travelling show to keep the criminal elements at bay. We’ll get to more of that in a minute.

Circuses and Traveling Shows

In the 1800s, circuses and other traveling shows often had a mixed reputation. They were perceived as both a source of wonder and entertainment and as gathering places for unsavory characters looking to take advantage of the crowds. The transient nature of these traveling shows also led to a perception of lawlessness and disorder, as they were not rooted in the communities they visited.

Show proprietors were charismatic showmen, with a knack for sales and marketing, transformed circuses into respectable, educational spectacles to combat this negative image. Ministers endorsed the shows as virtuous. Pinkerton detectives were brought in to travel with the shows and protect circusgoers from grifters, pickpockets, and other thieves—most of whom a seasoned Pinkerton would have recognized on sight.

The first embedded Pinkerton Detective was Thomas A. Gallagher, who traveled with one of the biggest circuses of the day from 1880 to 1883. Gallagher may have been the first, but he wasn’t the last. Pinkertons were embedded in all the notably and large traveling shows and became so much part of the circus culture that they were even listed with the regular employees in the route books published at the end of the season, and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was no exception. Pinkerton detectives traveled with the Show from 1884to 1908.

The One and Only Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, founded by the legendary William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody in 1883, was a traveling outdoor spectacle that brought the drama and excitement of the American frontier, captivating audiences across the United States and Europe. Cody, a former soldier, bison hunter, and showman, leveraged his fame and experience in the American Old West to create a show that featured a mix of action-packed performances, including wild animal displays, trick shooting, rodeo events, and theatrical reenactments of famous battles and western scenes. The show was a cultural phenomenon that had a profound influence in pop culture, often romanticizing the conquest and settlement of the West.

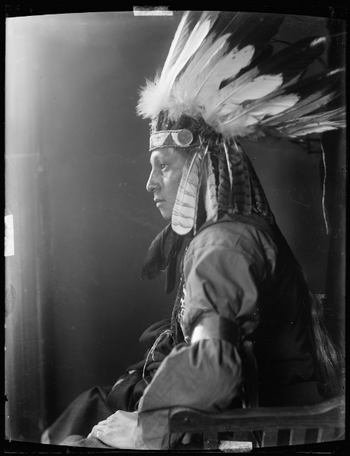

The Wild West Show was featured a diverse cast, including cowboys, Native Americans, and later, performers from around the world in the "Congress of Rough Riders of the World." Women like sharpshooter Annie Oakley – who could outshoot most men -- also played significant roles, challenging gender norms of the time. To his credit, Cody paid women in his show equal to what he paid men.

The 1900 Tour Specs and Logistics

The operational intricacies of the show were nothing short of astounding, incurring daily costs as high as $4,000. A culinary brigade provided of three hot meals daily for the 547 cast and crew members, prepared on sprawling twenty-foot ranges. The show was self-sufficient, producing its own power and maintaining a dedicated fire brigade.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show train consisted of 40 railcars, including 16 flat cars for transporting 35 baggage wagons, two ticket wagons, two band wagons, two generators for electric lights, two artillery pieces with caissons, one stagecoach, two covered wagons, and three buggies. Additionally, there were 15 cars for livestock, carrying 230 animals used to pull the wagons, and nine sleeper cars to accommodate the Show’s cast and crew during their unforgiving and relentless travel schedule. As for accommodations during extended stays, cast and crew found respite in canvas wall tents.

The Show required at least 11 acres for setup, with the main tent alone covering an area of 201,000 square feet. Nearly 23,000 yards of canvas was used in the construction of the tents, and an estimated 20 miles of rope were used around the show.

From the Show’s initial departure from Bridgeport, Connecticut on April 23 to the Show’s closing in Memphis, Tennessee on November 3, 1900, the caravan traveled 11,649 miles on 48 distinct railroad companies, covering 24 states and 135 cities, referred to as stands. Over the course of the show’s 194-day tour, there were 335 performances. After 14-day stand at in New York City, the show moved to Brooklyn and then to Philadelphia, each for six-day engagements. All others were all one-day stands.

In most places, the show would arrive in the morning, as early as 4 am and as late as 9:30 – although there is instance noted in the year’s route book where a large back up on the rails delayed half of the cast and crew until 11 a.m. Once the show arrived, the work began. All the cars were unloaded and the tents erected on the show grounds. There would be a parade and two two-hour performances at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. respectively. Then the whole show would be struck, loaded, and moved overnight to the next town.

April 23 — The Grand Opening

The Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show inaugural parade took place on a bright and sunny Monday, April 23 on the streets surround Madison Square Garden. That same afternoon, performers and crew fine-tuned their acts during the last dress rehearsal before the evening's main event. The evening performance, which played to a packed audience, saw the return of the crowd-pleasing highlights from the previous season's lineup and featured fresh elements, electrifying audiences and igniting nostalgia for the Old West. It also drew a certain criminal element, seeking a quick buck.

Pinkerton Detective William H. Minster, from Pinkerton’s New York Office, was assigned to the Show and mentored by Pinkerton Assistant Superintendent J.W. Rogers, who had previously held the same position for years with the show. Minster learned that his primary duty was to protect show patrons and visitors from theft and other crimes, as well as to monitor the show's employees for any irregularities.

Minster was also furnished with a rogue’s gallery, photographs and descriptions of criminals —notably pickpockets, sneak thieves, con men and sure-thing gamblers — that followed the big shows looking for an easy score.

Minster received varying levels of cooperation from local authorities, ranging from enthusiastic to non-existent. In towns with a high presence of criminals Minster's ability to take action was limited unless he witnessed a crime or had an arrest warrant.

Upon arriving in a new location, he would immediately request assistance from local law enforcement and provide them with complimentary show tickets for their families, always being cautious to prevent the passes from being resold. Apparently, it was something to be cautious about.

“On arrival in a city or town I always first thing in the morning called at Police Headquarters, the office of the sheriff or marshal in authority and made a request for a detail of a detective, sheriff or marshal to assist me in rounding up suspects and prevent the operations of criminals of all types that may be following the show,” Minster wrote in a lengthy essay the season ended. “After making the necessary arrangements with the authorities I made a detour of the town and along the line of parade to designate suspects.”

He would return to the show grounds for the duration of the performances, making the rounds in between and after the evening performances, ending at the train station when the show was loading onto the trains. His vigilant eye never wavered from dawn until the train pulled out of the station.

Ticket Speculators

"I never had much trouble keeping the show grounds clean but covering the city or town railroad stations, etc., was a bigger proposition, particularly when the authorities were lukewarm," Minster reported, noting that in that ticket speculators, aka “scalpers,” were the main issue in New York and also during the first two months of the tour.

Minster's efforts to curb ticket speculators was complicated by the show's own ticket sales tactics. The show's agents sold 50-cent tickets for 60 cents, granting early access to performances, a move that was criticized by both patrons and authorities. The speculators leveraged this controversy, selling their own overpriced tickets and citing the show's practices to justify their actions.

There were two ticket speculators, in particular, one known simply as Leonard and the other George L. Morrell, both suspected of colluding with a show insider to sell illicitly obtained tickets. Despite being frequently thwarted by the authorities, the speculators persisted, following Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show from city to city.

Soon enough, suspicion fell on ticket taker Star L. Pixley, who was observed by the Show's Manager Ernest Cooke and Treasurer Jule Keen pocketing tickets during a performance in New Haven, Connecticut on June 26.

“Cook and Keen were seated just inside the entrance to the show and when I joined them they informed me they saw Pixley put tickets in his coat pocket instead of the box when he thought he was unobserved, so I decided to act at once and as I was very friendly with Pixley,” Minster noted. “I put my hand in his pocket and said, “Give me a match, Pix,” and drew from his pocket a bundle of tickets he had been holding out. They were under a rubber band when I did that.”

Pixley's meek plea, "Cheese it, don't," confirmed his guilt.

He was arrested, confessed, and implicated Dan Taylor, the Show's boss blacksmith, as the intermediary with the speculators. Following their arrests, Pixley was found with a significant amount of cash — some $150 and 75 tickets — while speculator Morrell possessed $137 in cash and letters. Despite strong evidence, they were initially released on a $150 cash bond. Colonel “Buffalo Bill” Cody and the management insisted on a rigorous prosecution for conspiracy. Minster and Jose H. F. Quaid, the Business Representative, stayed in New Haven to oversee the legal proceedings, missing subsequent show dates. On July 2, all four men, represented by lawyers, pleaded guilty but faced only a $75 fine plus costs — a lenient sentence that Minster viewed as a "rank miscarriage of justice."

July 3 — The Gamblers

In Watertown, NY, on July 3, Minster faced a new challenge as he rejoined the Show: a pair of gambling mobs from Chicago and Detroit that followed the show. These gamblers set up their rigged games in towns along the show's route. While the detective succeeded in halting their operations in several places, other towns allowed the gamblers continued their activities unimpeded. In such towns, Minster warned local authorities that any negative attention drawn to the Show due to these crooks would be met with full disclosure to the press.

The situation escalated when a mob of the gamblers brazenly operated on the route to the show. After a defiant response to the detective's order to disperse, the mob's spokesperson retorted that the show had no authority over them since they were not on show property.

After a defiant response to the detective's order to disperse, he enlisted the show's canvas men to disband the gamblers.

“The canvas men did a thorough manner and the sure-thing gamblers were a battered, sad and wiser lot when the canvas men got through with them. Later as they were leaving town, they accused me of giving them a tough deal,” Minster reported.

July 29 — The Detroit Disaster: A Harrowing Train Collision

As if any traveling show would say it was all business as usual, most days were rather routine. A few of the cast experienced minor injuries in the course of performing. There a short stint in June when a large number of the cast and crew fell ill, most recovering quickly once medical aid was brought in. The route book noted that a few were sent to local hospitals in different cities, rejoining the Show when the recovered.

While that seemed par for running a large and formidable traveling show, there was also two notable incidents that occurred during the tour.

The first occurred on the morning of July 29, amidst the bustling rail yards of Grand Haven in Detroit, the Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show train was maneuvering through the city towards Milwaukee Avenue and Dequindre Street when disaster struck. The train reversed down the tracks, while an oncoming freight train traveled toward them on the same line. The freight train engineer sounded its whistle, yet it went unheeded by the show train's engineer. Despite noticing the impending danger, the train’s conductor could not prevent the inevitable crash, although the freight's engineer did manage to reduce speed significantly before impact.

The collision was catastrophic. The force of the crash drove the caboose into the front of the freight engine, shattering it against Car No. 56. The car was crushed, its occupants entombed amidst a chaotic blend of splintered seats, shattered glass, and broken flooring. Miraculously, the caboose's obstruction caused it to vault onto the roof of a sleeper car, an event that likely spared many lives.

Ed Sullivan, one of the show's personnel, was the first to be extracted from the wreckage. Despite the swift arrival of an ambulance, he declined medical hope, requesting only relief from his agony. Tragically, he succumbed to his injuries shortly after arriving at the hospital. Two more members of the show passed away in the days following the collision.

Remarkably, the remaining injured parties recovered from their afflictions, which largely comprised bruises, lacerations, splinter injuries, and contusions.

Joseph P. Quaid, the business manager who was aboard the car ahead of Car No. 56, took swift action to coordinate aid for the injured at local medical facilities. Once the wrecked caboose and the destroyed sleeper were detached, the show train resumed its journey to Pontiac.

The following day, the Show moved to Pontiac, MI where there was another accident. Wagon 12 was hit by a streetcar. It was slightly damaged, and there were no injuries. The Show resumed on Monday, July 30. The route book stated that the “weather clear” and “business big.”

August 20 — The Riot in Prairie du Chien

The second incident occurred on August 20, a sweltering summer evening. The quiet town of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, erupted into a tumultuous “miniature” riot. It started in a saloon — one of 20 in the town — where a few of show's cast, fresh from their afternoon performance and thirsty for refreshment, ran afoul of a bartender over an unpaid tab several hours later. Tempers flared, and when the bartender brandished a pistol, the cowboys didn't back down — they snatched the firearm and a scuffle ensued.

The commotion spilled into the streets, drawing an armed policeman into the fray. The situation quickly escalated as the officer's attempt to detain the rowdy bunch was met with resistance and a chase down the street. His shot rang out, striking a cowboy and igniting a full-blown riot. Buffalo Bill's cavaliers squared off against an incensed mob of townsfolk.

“As violence and property damage increased, someone sent a telegram to the governor of Wisconsin, who wired Cody in return, threatening to send in the National Guard,” wrote Ray R. Behrens, author of Buffalo Bill in Iowa: Tales of a Western Folk Hero.

“Unaware of all the commotion, Buffalo Bill had retired for the night. After reading the wire, he strapped on two loaded pistols, and shouted angrily, ‘Get my horse!’ Arriving in town, he used a whistle to summon his men and ordered them to fall into formation. Then, as if nothing had happened, he marched them silently back to the grounds,” Behrens wrote.

By dawn, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show had vanished.

The riot in Prairie du Chien was a fleeting but fiery clash that burned itself into local lore — a night when the Wild West truly lived up to its name, and Buffalo Bill, with a mix of stern authority and showbiz flair, restored peace to a town pushed to the edge.

The route book downplayed the event as a side note of the stay, “Business fair. A drunken deputy-sherriff caused a good sized row on Monday evening by pulling a gun on some of the riders. All hands instantly jumped in, and in the general excitement, Chas. Triangel and Harry Cinq-Mars, both of the Artillery detachment, were shot. Some badly-scared local authority telegraphed for the militia, but the trouble quickly ended and the performance when on as usual.”

The injured showmen were sent to the Improvement Hospital in Chicago.

Minster later reflected on the bedlam with cool detachment, “While it lasted it was an exciting affair, something the natives of the town had probably never before experienced. I kept out of the affair and was in no way involved.”

Crooks and Suspects from Rogues Galleries

Over the course of the tour, Minster reported over 100 crooks and suspects to the authorities and identified a number of them from photos furnished by the Agency and from photos he saw in rogues galleries in the different large cities and towns. Among them Richard “Windy Dick” Preston, “Fainting” Bertha Libbeke, and the infamous Thomas Geohegan,

Richard Preston

Richard "Windy Dick" Preston, a notorious and cunning pickpocket from Chicago, once gave his word to William Pinkerton that he would steer clear of any spectacle under Pinkerton’s protection, including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Known within the Agency by the codename "Airstone,” Preston had a reputation for his solo acts of thievery, often slipping stolen wallets into the pockets of unsuspecting bystanders to evade capture upon being designated and searched by law enforcement. His methods were sly, his movements quick, and his presence at any event was a sure sign of trouble brewing.

Minster, with a keen eye, described Preston as a man in his mid-40s, standing about 5'6" tall, weighing around 150 pounds, with a medium build, light brown hair, and brown whiskers.

"I saw a man in the crowd along the line of parade whom I thought resembled the photo of Preston. He saw me at the same time, hurried away between vehicles in a parking space in which there was a saloon and small country hotel," Minster recalled. “I was right after him. He went right through the bar room and evidently out by another entrance and disappeared.”

This wasn't their first encounter—Minster had spotted him before but hadn't gotten a good look. Now, with Preston's hasty retreat, Minster was certain of his identity and from then on was on high alert, conducting early morning patrols in each new town the Show visited.

When the Show rolled into Grand Rapids, MI, August 2, Minster's vigilance paid off. Spotting Preston near the railroad station and shadowing him to a restaurant, Minster wasted no time in alerting the authorities. Although it was too early for detectives at Police Headquarters, uniformed officers quickly responded and apprehended Preston.

Despite Preston's protestations that he wasn't tailing the Show, his presence in multiple towns where the Show performed was more than a mere coincidence. This elusive pickpocket, who had been a thorn in the side of the Agency since the mid-1890s, when he was designated following the Show as well as the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

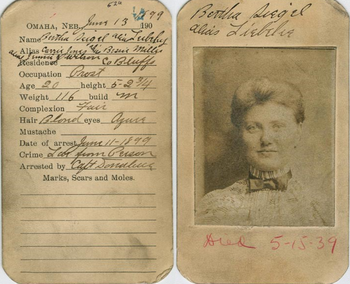

Fainting Bertha

Fainting Bertha, born Bertha Libbeke, was one of the Midwest’s most notorious pickpockets. At the young age of 20, she had already developed a reputation for her cunning tricks, which involved feigning fainting episodes to distract and rob unsuspecting gentlemen. Her technique was simple yet effective: she would target a well-dressed man, often one sporting a diamond-studded lapel pin, and upon stumbling into him, she would faint. As the chivalrous victim came to her aid, Bertha would swiftly relieve him of his valuables and wallet. It was said that Bertha could lift anything without raising suspicion.

Bertha's infamy spread across several states, including Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Iowa, where she was living at the time. Law enforcement was well aware of her antics and various aliases. Her mugshot graced the walls of most law enforcement agencies in the Midwest.

When the Show made a stand in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 8, the local detective assigned to work alongside Minster designated her when she came to the afternoon show.

"I put her out as soon as she had entered," he recounted, banishing her from the show and cautioning her to steer clear of any city where the Show erected their tents. "And, I told her it was useless for her to go into one of her phony fainting spells. She made a very feeble protest.”

Thomas Geohegan

Thomas Geohegen, Agency codename “Omstone,” was a known figure to the Pinkerton detectives, a "persistent follower" who, along with his “mob,” alternated between tailing Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show and other prominent traveling shows of the era that frequently made stands in neighboring towns. Geohegen’s presence was a specter of potential trouble, a challenge to the security of the events and the safety of their patrons. During one such encounter Minster spotted Geohegen working the crowd.

“I saw him working the cars plying between the town where this show was making a stand and a town about 5 miles distant where another show was having an engagement. He saw me as soon as I spotted him. He another of his mob jumped a car bound for the other town,” Minster recalled. “I did not see him after that for some time, but at St. Joseph, MO, [on September 25], between the afternoon and evening performance in making a tour of saloons, restaurants, and such I saw him and Ed Morgan, alias Watson, a burglar, seated at a table in a saloon.”

Minster immediately notified local law enforcement and Geohegen and Morgan were placed under arrest.

“Geohegan became very abusive and made the remark of having put one Pinkerton man out of the way and intimated the same thing would happen to me,” he stated.

William A. Pinkerton himself had warned of Geohegen's dangerous nature, advising the detective to avoid confrontation and instead to report him to the authorities. This advice was heeded, and when the Wild West Show reached Dallas, Texas, a couple of weeks later, the detective's vigilance paid off once more. Amidst a lineup of eight suspects arrested at the railroad station, Geohegen's familiar face emerged.

As minister walked in front of the line up, Geohegen whispered, "Don't Rap. Don't Rap."

When the show reached Dallas, TX, a couple of weeks later, where the State Fair was on, Minster learned that eight suspects had been arrested the night before at the railroad station. The 8 suspects lined up for me and among them was Geohegan, Watson, and others I had marked as suspects. As I went along the line, I designated them to the officers and when I got to Geohegan, he muttered in a low tone, “Don’t Rap. Don’t Rap.”

“I roasted him properly to the authorities because of the remark he made to me in St. Joseph,” the detective declared, recalling the sharp exchange. He immediately pointed to Geohegan said, “That big bum has been jumping in on me from time to time and he and his mob have given me a lot of trouble, he’s an old timer.”

Two days later on October 13 when the show was making a stand at Paris, Texas, the Assist Chief of Police and one of his detectives called on Minster to inquire whether I had seen Geohegan or Morgan. They had warrants for both men — all eight suspects in the Dallas lineup had been released on habeas corpus proceedings.

“But I did not see either of them after that,” he said.

November 3 — All Good Things Must Come to an End

The show closed at Memphis, Tennessee, on the night of November 3. Minster boarded a special train at 1:20 a.m., November 4, headed for home.

In his final report on the show, Minster wrote, “My experience with the show was long hours, hard work, plenty of excitement and a great strain of mostly one night or rather one day stands leaving most towns after midnight. My detail with this show was a wonderful experience, full of exciting events and very instructive…It also afforded me an opportunity to know criminals from all sections of the country. I could write as many more pages of interesting events that occurred during the tour of the show.”

While this was Minster’s first and last tour with the Show, he continued his career with Pinkerton’s and mentored new detectives for the Show until 1908, passing on his experience. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show continued to tour until 1916. Col. Cody passed away two months after the Show closed.

SOURCES

Behrens, Roy R. "Buffalo Bill in Iowa: Tales of a Western Folk Hero—and His Doppelganger." Iowa Source, 4 Aug. 2020, www.iowasource.com/2020/08/04/buffalo-bill/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Dyrud, Marty. History talks from Prairie du Chien: Volume 1 (Prairie du Chien, Wis.: V. Dyrud, [1985]) https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/tp/id/81342/rec/1. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Davidson, Shayne. "Fainting Bertha." Captured and Exposed, 19 Mar. 2021, https://capturedandexposed.com/2021/03/19/fainting-bertha/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Fees, Paul, Former Curator. "Wild West Shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West." Buffalo Bill Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, centerofthewest.org/learn/western-essays/wild-west-shows/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Meyer, Ann. "Buffalo Bill Wild West Show of 1900 Was Quite a Spectacle." HTR News, 4 Aug. 2017, www.htrnews.com/story/life/2017/08/04/buffalo-bill-wild-west-show-1900-quite-spectacle/541060001/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Nebraska State Historical Society. "Bertha Liebbeke." History Nebraska, https://history.nebraska.gov/exhibit_mug_shots/bertha-liebbeke/#:~:text=Bertha%20Liebbeke%20earned%20the%20reputation%20of%20being%20one,helpless%20victim%2C%20pretending%20to%20faint%20into%20his%20arms. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Pinkerton administrative files: Employee William H. Minster career. (1900). Pinkerton's national detective agency, part A: Administrative file, 1857-1999; employees () Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/archival-materials/pinkerton-administrative-files-employee-william-h/docview/3051686414/se-2

Prairie du Chien Area Chamber of Commerce, Inc. "History." Prairie du Chien Area Chamber of Commerce, Inc., www.prairieduchien.org/history/. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Route Book Buffalo Bill's Wild West 1900: Containing Also the Official Routes, Seasons of 1895, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1899." Milner Library, Illinois State University, digital.library.illinoisstate.edu/digital/collection/p15990coll5/id/3086/rec/1. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.