February 7, 1963 — On this day in history, thousands of art enthusiasts gathered at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to witness the unprecedented and highly anticipated unveiling of one of the world’s greatest art treasures: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

In this landmark event, the Pinkertons played a small but crucial role in the secure transportation and protection of the Mona Lisa during its historic journey from the Musée du Louvre (Louvre Museum) in Paris, France to the United States, which began several months earlier.

In the spring of 1962, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy presented André Malraux, the French Minister of Cultural Affairs, with an idea during his official trip to Washington, D.C. She told him, “I would love to see the Mona Lisa again and show her to the Americans.”

Malraux reportedly replied, “I’ll see what I can do.”

By the year's close, the Mona Lisa, also known as La Gioconda (Italian) and La Joconde (French), was in the United States at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. awaiting her grand unveiling to the American public.

Understanding the logistical challenges of transportation

While some at the Louvre's research lab thought the idea of shipping the Mona Lisa was “extremely foolish,” the team, nonetheless, faced the monumental task of safeguarding the painting for her transatlantic voyage. While the Mona Lisa was in fairly good condition for her age, the painting was quite fragile. The poplar panel on which the portrait was painted showed some evidence of warping and deterioration. And the research staff knew how sensitive to differences in temperature she was. The protection of Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece required security measures that had never been attempted before.

Their innovative approach led to the creation of a specialized temperature-controlled case inside a fireproof and watertight container to protect the painting's delicate layers from vibrations and prevent any contact with external surfaces. This container would then be placed inside a large wooden crate.

Further, striking a critical balance between portability and security, the team designed the crate to be compact enough for two people to carry but too large and heavy for one person to carry, deterring theft.

While some at the Louvre's research lab thought the idea of shipping the painting was “extremely foolish,” the team, nonetheless, faced the monumental task…

The crate not only secured the painting but also protected the interests of France in the event of an unforeseen maritime disaster. Should disaster strike, the crate was unsinkable and marked with the French flag, asserting its national ownership to prevent legal disputes over maritime salvaging rights.

The complexities of the Mona Lisa's transport and display were not limited to its physical journey. The expectations for the painting’s security upon arrival were just as stringent. The Louvre’s team demanded a bank vault at the National Gallery with an independent air-conditioning system for resilience against power outages or strikes, establishing a benchmark mark for protective measures surpassing even those for ancient Egyptian treasures.

The galleries where the painting would be displayed also needed to recreate the ambient temperature and humidity of the Louvre. These demands underscored the Mona Lisa's significance and the lengths that France was willing to go to ensure its preservation.

Interestingly, the demands also included emergency connections with hospitals or the Pentagon, for added assurance.

The Mona Lisa’s journey to the United States

Early in the morning of December 14, 1962, uniformed Louvre Museum staff meticulously removed the Mona Lisa from the Grande Galerie and placed the painting into the specialized travel container and crate. The crate was carefully loaded into a reinforced truck equipped with vibration-dampening springs to minimize jostling and protect the painting's delicate pigments. The truck, flanked by three police vehicles and a protective escort of six police motorcycles, then embarked on the 110-mile journey to the Paris-Le Havre dock.

Accompanied by nine Louvre guards and two museum officials, the crate containing the painting was discreetly and solemnly loaded onto the ocean liner S.S. France. It was bolted to both the bedframe and floor of cabin M-79 and placed under the cover of a heavy, dark gray wool blanket.

The painting was also placed under the cover of some of Pinkerton’s best agents…

The painting was also placed under the cover of some of Pinkerton’s best agents, who maintained an unwavering 24-hour watch over the precious cargo.

The extra security on the ocean liner didn’t go unnoticed by passengers. Concerns arose that the ship might be transporting a clandestine Cold War device, potentially nuclear.

However, under pressure and against the wishes of the French officials, the S.S. France’s captain disclosed that the only significant cargo was the famed painting itself. The news sparked festivities among the crew and passengers. The ship's culinary team crafted special dishes to honor the artwork, and passengers threw Mona Lisa-themed costume parties, celebrating into the early hours.

Protected in the motorcade from New York City to Washington, D.C.

On December 19, after five days at sea, the SS France arrived in New York Harbor, accompanied by the United States Coast Guard. The ocean liner docked at Pier 88, where it was met by local, state, and federal officials.

The transfer of the Mona Lisa from the ship to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. — under American President John F. Kennedy's directive and the protection of the Secret Service — was conducted with high-level transportation security measures. A Secret Service agent, armed and concealed in an overcoat, accompanied the painting inside a secure, climate-controlled van.

The New York Police Department cleared city streets and tunnels in advance and stationed sharpshooters on rooftops in a few strategic locations as a precaution. Escorted by additional Secret Service agents, NYPD officers, and state troopers from New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland with lights and sirens, the painting’s motorcade traveled 250 miles from New York City through icy winds and subfreezing temperatures to the National Gallery in Washington, without stopping — even when road conditions forced the motorcade to slow to 5 mph/8 kph on the capitol’s streets. Soon enough, the Mona Lisa was delivered without incident to a contingent of heavily armed guards, who carefully transferred the painting to the Gallery's basement.

A Secret Service agent, armed and concealed in an overcoat, accompanied the painting inside a secure, climate-controlled van…

Once inside, museum curators locked the painting inside the steel-doored Vault X, while guards and a small detail of Secret Service agents monitored via closed-circuit television (CCTV).

The next morning, the painting was extracted from its aluminum-and-vinyl carry case and delicately positioned atop a custom stand, marking a critical juncture. Donning protective gloves and a laboratory coat, a museum curator meticulously photographed the painting from various angles and scrutinized the poplar panel through a magnifying lens typically used by optometrists.

Despite the travel and unforeseen weather, the Mona Lisa was unchanged. The painting was placed within its gilded oak frame and shielded behind an inch-thick, double layer of bullet-resistant glass, where the ambient temperature remained a constant 62°F/16.66°C.

It was reported that the painting was insured for approximately $100 million dollars.

The Mona Lisa’s visit at the U.S. Capital

On January 8 under the watchful eye of the U.S. Marines, appointed by President Kennedy, the painting was unveiled with fanfare and speeches at a ceremony attended by the President and First Lady, Minister André Malraux as well as over 2,000 politicians, dignitaries, and other special guests.

“That the possession of masterpieces, today, imposes great responsibilities, everyone knows,” said Malraux. “There has been talk of the risks this painting took by leaving the Louvre. They are real, though exaggerated…”

President Kennedy further commented, “We in the United States are grateful for this loan from the leading artistic power in the World, France…I must note further that this painting has been kept under careful French control, and that France has even sent along its own Commander-in-Chief, Monsieur Malraux.”

In the days following, when the exhibition was open to the public, the National Gallery experienced an unprecedented influx of visitors, with lines of people 10 deep extending nearly a third of a mile. The guards, overwhelmed by the sheer volume of attendees, were unable to tally them accurately with their handheld counters. However, when the Gallery’s exhibition closed on February 3, it was noted the painting received over 518,000 visitors.

Detour to The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Initially, the agreement was for the Mona Lisa to be exhibited exclusively at the National Gallery.

Unexpectedly, while the painting was en route to the U.S., plans evolved, permitting the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to also exhibit the celebrated piece.

On February 4, the Mona Lisa made her covert entrance at The Met, sheltered once again wrapped in layers of security — including two Secret Service agents, two NYPD detectives, and two eagle-eyed museum guards. The painting was taken to one of the Western European Arts storerooms, where it remained under “intense surveillance” until the official unveiling ceremony on February 6.

“The security for the Mona Lisa was novel,” noted Thomas Hoving, one of the Met’s former directors, who was a medieval department curator at the time, but even the state-of-the-art surveillance did not keep the Mona Lisa from incident.

In his autobiography, Hoving stated that the painting was set on an easel in the center of a secured storeroom with lights trained on it, and one morning he arrived at the museum to find two of his colleagues rushing around with towels.

Due to an undiscovered reason, a ceiling fire sprinkler shattered its glass vial, causing water to “rain down.” The security team monitoring the Mona Lisa via CCTV outside the storage room did not see the water on their black-and-white screen, and the leak wasn’t discovered until the door to the room was opened in the morning.

But the Mona Lisa was okay. According to the onsite Louvre official, the lady was undamaged, as the double-layered bulletproof glass over the painting safeguarded her like an impermeable raincoat.

Hoving also revealed that the event was kept secret from the public, except for the disclosure he made in his book years later.

Record-setting visitors and safe travels home

The museum staff mounted the Mona Lisa against a backdrop of red velvet on the Spanish choir screen dividing the Medieval Sculpture Hall, one of the largest rooms in the Museum. Just like the display at the National Gallery, the painting was flanked by two U.S. Marines in dress blues and monitored by museum security, both uniformed and undercover.

After waiting sometimes for hours in New York’s bitter cold, visitors were ushered into the hall for nothing more than a glimpse — a pause of about four seconds, according to The New Yorker — to accommodate the continuous flow of spectators. Immediately following their viewing, guests were directed to exit the building to the museum's parking lot. The Met's records indicate that on one particular day, a record-breaking total of 63,675 visitors gazed upon Mona Lisa.

The exhibition closed on March 4. The museum noted that some one million people walked through the museum’s doors to see the Mona Lisa. (For perspective, the painting sees approximately eight million visitors per year at the Louvre.)

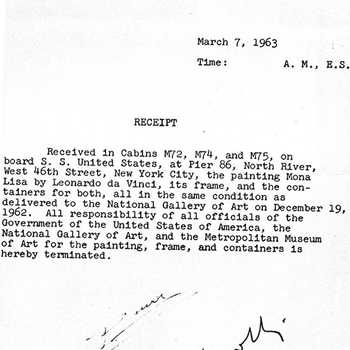

On March 7, the Mona Lisa was securely repacked in its travel container and crate and placed on the S.S. United States for her voyage back to France. The Mona Lisa was successfully reinstalled at the Louvre on March 12, 1963.

William Pinkerton and Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency had a historical connection to the Mona Lisa long before covert agents escorted Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece across the Atlantic from France to the United States in 1962. There was that time the artwork went missing from the Louvre – that was Monday, August 21, 1911. Read more about how the Pinkertons pursued clues around the globe and publicly defended a swindler accused of stealing the Mona Lisa in another historical blog: Missing! The Mona Lisa and the Detective.