The Pinkertons had a historical connection to the Mona Lisa long before we escorted Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa across the Atlantic from France to the United States. When the artwork went missing from the Louvre on Monday, August 21, 1911, Pinkerton was on the case.

It was a typical Tuesday morning when the news broke. The painting was not hanging in her usual place in the Louvre’s iconic Salon Carré. On the morning of August 22, a battalion of about 60 detectives arrived on the scene to investigate. After finding the Mona Lisa’s frame and interviewing witnesses, the detectives determined the painting was stolen sometime between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m. the previous day, when the museum was closed for cleaning and security was lax—although approximately 800 workers, including museum officials, guards, workmen, cleaners, and photographers were going about their business at the museum.

There were few clues as to what happened. A fingerprint expert recovered a print on the frame but couldn’t match it to anything in the database. Another Louvre employee reported some suspicious activity but couldn’t remember faces. Not a trace of the painting was found.

And then the world found out the virtually unknown painting had been stolen.

Pinkerton on the case of the missing Mona Lisa

Within a few days, the search broadened. William A. Pinkerton — the Agency founder’s son and head of the Western Office of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency in Chicago, Illinois — went to Paris. He traveled for months in his quest to recover the painting, touring Europe and other continents whenever fresh clues were unearthed.

Months of mystery fueled wild theories about the Mona Lisa’s disappearance, with some media outlets and amateur detectives suggesting nefarious political motivations. Even French poet Guillaume Apollinaire and his artist friend Pablo Picasso came under suspicion and were questioned. Both were later exonerated.

Rumors of sightings spanned from Argentina to Japan, the United States, and all over Europe, yet after two years without leads, fears grew that da Vinci’s iconic masterpiece might be gone forever.

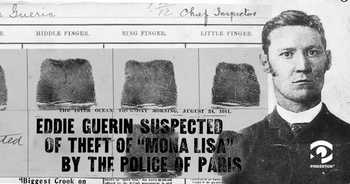

An early suspect — Eddie Guerin

One early suspect was Eddie Guerin, one of the most notorious thieves and confidence men of the early 20th century, known for his daring heists and even more daring exploits. He had been convicted of various crimes in the United States and Europe and had been sentenced to life at the infamous French penal colony of Devil's Island, off the coast of French Guiana in South America. Guerin claims to be the only one to have escaped the reportedly inescapable penitentiary — but that is a story for another time.

It was rumored that Guerin wanted to “get square” with the French government for his convictions by stealing the Mona Lisa. At least that’s what a South American businessman told the media after he heard it from the consular agent who said he helped Guerin escape from Devil’s Island. Allegedly Guerin wrote the agent a letter stating his conquest.

A fortnight later, the news came that the painting had indeed been stolen.

According to the businessman, a second letter to the agent stated that “Mona Lisa” was not destroyed but would never again fall into the hands of the French government.

Pinkerton’s history with Eddie Guerin

Pinkerton, known as the world’s greatest detective, called the rumor “rot.”

“Guerin wouldn’t go to France,” Pinkerton stated. “Detectives of that country would give their fingers to get hold of him. He is under conviction in that country of having robbed the Bank of France, and there is a life sentence hanging over him. France made a hard fight to have him extradited and failed, but they have never forgotten him. Guerin knows that. He is no fool, and he wouldn’t go back. He is the only man who is free today after having been sentenced to life on Devil’s Isle.”

This was not the first time Pinkerton interacted with Guerin. Pinkerton had known him from the time he began his career as a crook in Chicago. As a side note of interest, Guerin’s brother was a Chicago Police Department officer.

“Eddie Guerin has ‘turned straight.’ He did not steal the $500,000 ‘Mona Lisa’ painting from the Salon Carré in Paris. He is a respectable tradesman in London,” stated Pinkerton.

Rumors and more rumors

If the letters to the consular agent and the information therein were real, then they were simply part of a bigger con with Guerin and the Mona Lisa at the center.

As the story goes, Guerin was endeavoring to sell a copy of the Mona Lisa for $1,000,000. He had in mind a scheme — create a forgery on the pretext that it was the original and had been stolen. He had conceived the idea of a “thimble game” in which the Mona Lisa was the vanishing pea. Guerin’s mark was a Philadelphia millionaire whose judgment in art matters was exceeded by his enthusiasm in acquiring what should be the greatest gallery in the world.

The rumors said that Guerin smuggled the forgery into the United States through Canada and showed the would-be buyer. Negotiations dragged on and finally halted when the painting’s authenticity was questioned. Several experts scrutinized the painting, all declaring that the coloring was off. The Philadelphia collector declared that he would not pay $1,000,000 for a copy.

But then came the news that the Mona Lisa had been stolen. The mark reconsidered.

Once again, Pinkerton came to Guerin’s defense.

"Guerin was never in the art stealing game," said the detective. “Other crooks used to tell tales of that kind about Guerin, but they were all lies.”

Pinkerton even offered the name of another swindler — Patrick Sheedy, a well-known gambler who risked fortunes at the turn of a card — who was more likely to attempt such a con.

Years later, American reporter Karl Decker added another twist in a 1932 edition of The Saturday Evening Post. He theorized that a cunning swindler from South America allegedly orchestrated the creation and sale of six Mona Lisa replicas, with each unsuspecting purchaser believing they had acquired the one true original. But the Philadelphia collector was not among them.

The mystery of the missing Mona Lisa — solved!

In November 1913, more than two years after the Mona Lisa’s disappearance and more than another two months in Europe, Pinkerton told police that the painting had been stolen by persons with partners inside the Louvre. Certain criminals, he stated, had boasted they could obtain any piece of art they noted from the Louvre at any time.

It turns out that the theft was an inside job. But it wasn’t by an international art gang. Rather, it was by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman and former Louvre employee who had crafted the Mona Lisa’s protective frame. He had two accomplices, brothers Vincent and Michele Lancelotti. They all snuck into the Louvre on Sunday, August 20, and hid in a storeroom overnight. The next morning at 7 am, they exited the storeroom. Two of the thieves removed the painting from the wall in the Salon Carré and carefully removed the painting from her frame while one stood as a lookout. The brothers exited by a stairwell while Peruggia simply tucked the painting under his white apron — a garment worn by the hundreds of museum staff going about their day — and walked out. To be fair, he did encounter a couple of minor hiccups on his way out, like a locked door that a plumber helped him unlock. The security at the Louvre at the time was so lax that no one even noticed that the enigmatic and easily overlooked Renaissance masterpiece was missing for 26 hours.

Peruggia intended to return the painting to Italy, however, it became too hot too quickly. So, he concealed it within a false-bottomed trunk in his modest Parisian boarding-house apartment. Peruggia even evaded police suspicion despite being questioned twice. The police considered him inept and not a criminal mastermind. He bided his time for two years while the heat died down.

In late November 1913 under the alias “Leonard,” Peruggia answered a newspaper advertisement from an art dealer in Italy offering good prices on art pieces of all kinds. In his letter to the art dealer, he stated that had the stolen Mona Lisa.

A couple of weeks later in a Florentine hotel room, Peruggia unveiled the tantalizing sight — “La Giaconda” herself. The painting was authenticated, and a price negotiated. Except the buyers didn’t pay Peruggia right away. Instead, they took the painting and indicated to Peruggia that payment was forthcoming. Then they notified the authorities.

On the afternoon of December 11, 1913, the police apprehended the art thief at his hotel. His trial was brief. He pleaded guilty and served eight months.

Following a brief tour in Italy, the painting was returned to Paris on December 30, 1913, and rehung in Salon Carré. During the first two days after her return, more than 100,000 people flocked to the museum to view her. The Mona Lisa had just become the most famous painting in the world.

Nearly 50 years later, the Pinkertons played a small but crucial role in transporting the iconic painting in a cultural exchange from the Musée du Louvre (Louvre Museum) in Paris, France to the United States.

The painting’s journey and multi-city exhibitions were, in themselves, feats of innovation that fused art, science, and security in unprecedented ways — from temperature-controlled cases to unsinkable crates, reinforced trucks with vibration-dampening springs, strategically positioned sharpshooters along the rooftops of New York City, motorcades worthy of any head-of-state, state-of-the-art electronic surveillance, and around-the-clock protection by uniformed and covert agents alike. Read more about the Mona Lisa and the cutting-edge security that her journey possible.