Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency leaders long held the opinion that the holidays were one of their busiest times of the year, especially when it came to check swindlers and sneaks — who could blend into the bustling shopping crowds to ply their trade on shop owners and shoppers alike. And those with a particular talent were among the most successful in their trade.

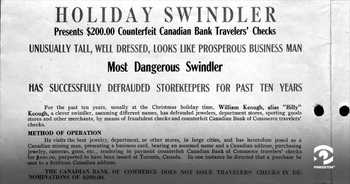

One forger, Lawrence Michael Farrell, aptly nicknamed “Christmas Keough” because he generally surfaced at Christmas, evaded law enforcement and the Pinkertons alike for the years between 1908 and 1918. William Pinkerton, head of the western branch of the Agency from 1884 until his death in 1923, placed Farrell second on his most dangerous forgers list.

Farrell, also known as Lawrence Keough, Billy Keough, O’Keefe, Wm. M. Lunbar, E.W. Howard, R.A. Bender, G. Dundas, H.H. Travers, B.E. McLeod, McKinnon, Paget, Dunham, Harry Harris, et al., had his first brush with the law in 1895. After an overturned conviction, Farrell spent the next several years refining his swindling techniques across the United States and Canada — which included his summertime schemes to defraud banks, farmers, hotels, widows, and realtors in the U.S.

“How Keough managed to evade capture for 20 years is simply inexplicable,” said Pinkerton Superintendent Herbert S. Mosher, while noting that the Agency pursued Keough for nearly decade of his criminal career.

A new start and a new name

According to Agency records, Farrell’s first bank swindle was in 1908 for a relatively small amount. In 1909, he used forged checks to swindle $1,600 from a Wisconsin bank and $1,500 from a bank in Louisville, Kentucky. (That’s approximately $52,000 and $49,000 respectively in today’s market.)

By 1911, Farrell emerged into the Jewelers Security Alliance’s purview when he swindled several jewelers with forged papers operating under the aliases Keough and O’Keefe. He was also involved in a wire-tapping scheme in Chicago and passed a forged draft from a Portland, Oregon bank.

Just before Christmas in 1912, Farrell entered the Canadian Bank of Commerce in Toronto, Canada, where he stated his intention of spending Christmas in New York City. He requested three $200 traveler’s checks. Before departing the bank, Farrell, who was using the name Keough and claiming to be a mining engineer, wished everyone a hearty and cheerful, “Merry Christmas.”

When interviewed later, the clerks commented on what a pleasure it was to do business with such a successful and affable customer.

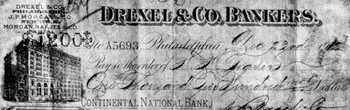

Before the close of the year, two of the traveler’s checks issued to Farrell were sent from jewelry stores in New York City to the Canadian bank, accompanied by a volley of forged traveler’s checks. Although most of the traveler’s checks were for $200, it was noted that one was written for $1,200. Bank officials quickly engaged detectives to trace Farrell, without success.

Same time next year

The following year, Farrell, now known as “Christmas Keough,” traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he swindled some eight banks, leaving with both cash and checks that he would use for future swindles.

Farrell then surfaced in the Christmas shopping rush in Boston, Massachusetts, setting his sights on Beantown’s jewelry stores. He used a different alias but the same modus operandi as NYC. Farrell would enter a store posing as a successful businessman — usually a mining engineer — and select an expensive piece of jewelry. It was reported that he was approximately 45 years old, 6’1” tall, weighing no more than 200 pounds, with dark salt and pepper hair, and grey eyes. He was immaculately styled, impeccably dressed, and well-spoken, sporting a distinctive Canadian or a delightful “Piccadilly” British accent. He would “saunter forth” so confidently and jovially that he was nearly irresistible. He would offer to pay for the jewelry with traveler’s checks and ask for the change in cash. If the clerk hesitated, Farrell would show them a letter of identification from the Canadian Bank of Commerce stating that Farrell had indeed purchased the checks in question.

The letter looked genuine — issued to Farrell when he purchased the original traveler’s checks but altered to Farrell’s current alias — and clerks honored the traveler’s checks, handing over both merchandise and change. Not surprisingly, Farrell also presented scores of checks drawn from other banks, including the eight in Philadelphia.

As soon as the Yuletide season ended, Farrell disappeared. Pinkerton records show he defrauded banks a modest $4,000, while others estimate Farrell netted about $85,000 in 1913.

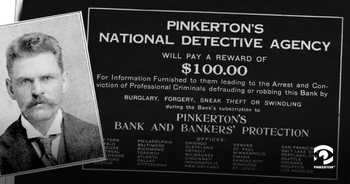

After three holiday seasons, and quite aware of the ongoing active threat, the Jewelers Security Alliance and a Chicago bank hired Pinkerton’s to apprehend this sneaky swindler. Almost immediately Farrell became a person of interest.

Successes and failures

In 1914, Farrell set to work in Chicago, Illinois, visiting nearly a dozen stores. At one store, Farrell, this time operating as A. Travers, cashed a forged check for $1,000, walking away with merchandise and change. That year, he pocketed about $35,000.

In December of 1915, Farrell returned to Philadelphia, where he bypassed banks and headed to a clothier where he successfully cashed one of his now-infamous $200 Canadian traveler’s checks. He attempted to purchase merchandise at another store in the city, but he was unsuccessful.

However, he wasn’t entirely unsuccessful in Philadelphia. The Jeweler’s Circular from December 1915 reported that most of Farrell’s forged checks that year were in the amount of $1,200 and one for $1,500 from the Continental and Commercial Bank of Chicago, one of Pinkerton’s clients.

A report received at the Agency’s New York office just after Christmas stated they believed Farrell left Philadelphia and went to Roanoke, Virginia, where a man answering Farrell's description had successfully altered a check for $1,800. While Farrell successfully evaded the Pinkertons, operatives were able to obtain a photograph of Farrell.

“Keough has been a master in covering his ‘getaways,’” said Pinkerton Superintendent Herbert S. Mosher. “We were on his trail 12 hours after he put over a job and ran a fine-tooth comb over every train departing from the city where he operated without obtaining the slightest clue to the man.”

The end of an era

In 1916, Farrell descended upon NYC as G.H. Meighan and despoiled the city’s most prominent department stores using both $200 and $400 checks, traveler’s checks and other forged papers.

It should be noted that because of Farrell, the Canadian Bank of Commerce discontinued issuing $200 traveler’s checks — but Farrell did not. Henceforth, every $200 Canadian Bank of Commerce traveler’s check was a forgery by none other than Christmas Keough.

The real Christmas Keough?

Throughout the years, the Pinkertons flooded tradespeople all over the country with circulars advising them to be on the lookout for Christmas Keough, doubling down their efforts during the holiday season. The circulars accurately described the swindler and, after 1915, included Farrell’s photograph and images of the fraudulent traveler’s checks. The challenge, according to Agency records, was the vast territory in which Farrell operated. They simply did not know in which cities Christmas Keough would strike.

A break in the case came on December 30, 1916, when a store clerk in St. Louis, Missouri, caught a man matching Farrell’s description and photo from the Pinkerton circular attempting to cash a $200 Canadian check, this one drawn on the Royal Bank of Toronto Bank. A competing detective agency — code name Poorwood — was quick to the scene and arrested Alexander P. Macauley.

Pinkerton officials, notified by informants of the arrest, immediately conducted their own investigation. Although Macauley’s description was similar, there were several important discrepancies, among them scars from Farrell’s boxing days and a comparison of Farrell’s and Macauley’s handwriting. Pinkerton officials were certain that Macauley was not Farrell.

“They most certainly do not have Keough in St. Louis,” said David Thornhill, Pinkerton's assistant general superintendent.

This was not enough to persuade retailers in New York from extraditing and prosecuting Macauley for forgery. Headlines around the globe declared the capture of Christmas Keough.

Not to be outdone

On April 28, 1917, while Macauley was in New York awaiting trial, the real Christmas Keough was still at large. “J.A. Paget” visited five prominent department stores in Chicago and cashed $200 traveler’s checks drawn on the Canadian Commerce Bank of Toronto.

It could not be proven, but some newspapers reported that Farrell re-emerged during the spring because he did not want another taking credit for his clever schemes. News of the Chicago forged checks gave pause to the prosecution’s investigator. He believed the prosecutor made a grave mistake. Not only was it impossible for Macauley to be in Chicago on the day in question, but it was also found that Macauley was a man of undisputed business integrity and the president of the Vacuum Oil and Gas Company of Toronto with large interests in Ontario. He carried a cash total of over $100,000 in banks with additional holdings and was able to demand unlimited credit, which was given without question.

The investigator stated that this case should not go to trial, because “some idiot might try to convict him.” He gave Macauley a handsome apology for all the indignities to which he had been subjected.

The case did go to trial, and Macauley was acquitted later that year. The entire process was costly to his pocketbook and health. He spent $30,000 in legal fees and suffered a paralytic stroke, which, it was claimed, was brought on by the shame and worry of the situation.

Farrell, however, went on to have an unusually busy holiday season, passing forgeries in St. Louis, New York, Chicago, and allegedly several other cities where he pocketed more than $25,000.

Person of interest

Following Macauley’s acquittal in October 1917, the Agency placed “wanted notices” in the November and December issues of The Jeweler’s Circular and Keystone Monthly, the jewelry industry’s most prominent trade papers, reaching almost every wholesale and retail jeweler in the U.S. They did the same the following year. The Agency also printed 1,000 additional copies of the circular to be sent to Pinkerton offices and distributed to their city’s most prominent retailers.

According to Agency reports, Farrell was shadowed by Pinkerton operatives throughout 1918. However, they were unable to make any arrests because they were never able to “catch him with the goods.”

When Farrell left Chicago for Pittsburgh in December, the Pinkertons notified the Pittsburgh and Altoona police departments and hurriedly redistributed circulars to retailers in those cities.

The trap tightens

On December 21, 1918, a man giving the name Harry Harris walked into a department store in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After selecting a $97 lady’s coat, he handed the cashier a $200 traveler’s check and received $103 in change. Before Harris had even exited the store, the store’s credit department saw the traveler’s check and compared it to the Pinkerton circular that had arrived just that morning. The manager approached the shopper and demanded the return of the coat and the $103.

“There must be some mistake,” stated the shopper.

“There’s no mistake here. Look at your picture and the picture of these checks,” the manager said, showing him the Pinkerton circular of Farrell.

Harris was indignant but returned the coat and money and left the store immediately.

Pinkerton’s Pittsburgh office was notified and deployed operatives to search the city and cover the train station. Just as the 7:20 train for New York was about to depart, Harris rushed through the train gates and boarded. He was shadowed by Pinkerton Operative William H. Shoemack, who later became the Superintendent of Pinkerton’s Cleveland and Detroit offices.

Harris had purchased tickets to New York but cut that trip short. When he disembarked early at the Altoona, PA station, Shoemack, along with the Altoona Police, made the arrest.

“Harris” used the same defense as Macauley, claiming he was a victim of mistaken identity, even offering as alibi an alleged arrest by Scotland Yard in the UK during one holiday season. This time there was no mistake. Harris was Farrell, aka Christmas Keough. The Pinkertons and other eyewitnesses positively identified him — by his moles, broken nose, broken knuckles, scars, and fingerprints.

“Christmas Keough has been caught at last. There is no doubt. He’s the man,” announced William Pinkerton. “This arrest demonstrates the persistency of Pinkerton. Each case is thoroughly investigated until every clue has been exhausted or the person responsible is arrested.”

Each case is thoroughly investigated until every clue has been exhausted or the person responsible is arrested.

The end of “The Holiday Swindler’s” reign

After Farrell’s arrest, authorities in Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York City promptly filed extradition requests, where he was identified by an overwhelming array of witnesses.

Consequently, the New York City district attorney’s office discovered a couple of Farrell’s stashes. One safe deposit box contained about $20,000 in stolen jewelry, $2,360 in cash, and a supply of lithographed $200 traveler’s checks from the Canadian Bank of Commerce as well as other forged checks from across the United States. Another safe deposit box contained some $26,000 in cash, about $4,000 in stolen jewels along with more forged checks.

Farrell’s New York City trial lasted one day. The jury deliberated for five minutes and returned a guilty verdict. He received an indeterminate sentence of one to 10 years at Joliet Prison in Illinois. He was paroled in December 1923.

Shortly after his release, he was once again arrested by the Pinkertons for the forgeries he committed in Boston 1913. He was sentenced to an additional 2-1/2 to 5 years to be served at the Massachusetts State Prison. When paroled in November 1926, he promptly disappeared.

One last con

In June 1927, a well-dressed, distinguished-looking gentleman, about 50 years old, called at the New York branch office of the Canadian Bank of Commerce and requested to cash $500 worth of travelers' checks. The bank manager said they were not able to cash the checks but could hold them for collection from the bank’s main office in Montreal. The gentleman agreed to call again in a few days to see if the checks would be honored. He left his name, “Dr. T. H. Lamar, Osteopathist #7 Dover St., Picadilly, London, England.”

It was found that the checks were forgeries of the batch purchased by Farrell years earlier. When questioned later, Dr. Lamar stated that he received the checks from an acquaintance in London, and regarding Farrell, “I never heard of that gentleman.”

“Lamar” was taken to police headquarters where his fingerprints proved beyond question that he was indeed the notorious forger. Farrell was returned to Charlestown State Prison later that year for violating his parole. He served the remaining years of his term and was released in 1930.

The police credited Farrell with swindling nearly $500,000 during his 20-year career, although the Jewelers Security Alliance estimated the total was closer to $1 million.

Since 1850, Pinkerton has been protecting businesses from holiday scams and preventing holiday season crimes.