This blog is a part of our Scouts and Spies series.

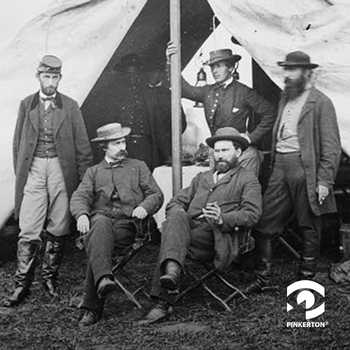

The Federal Secret Service, under the leadership of Allan Pinkerton during the Civil War, played a pivotal role in the North’s war efforts through innovative intelligence operations. The real heroes of the Secret Service were the scouts and spies whose endeavors often took them behind enemy lines to gather vital information. Their bravery, combined with reconnaissance, decoding of intercepted messages, and social engineering significantly contributed to the strategic successes of the Union.

One such figure was John C. Babcock, a Civil War scout and mapmaker for the Federal Secret Service.

Architect, patriot, sharpshooter, and interrogator

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, the 24-year-old Babcock, an accomplished pre-war architect living in Chicago, volunteered for the Sturgis Rifles, an Illinois sharpshooter unit performing special missions under the command of General George B. McClellan. Initially, he was assigned to the overcrowded Central Guard House, a temporary detention center for disorderly soldiers in Washington, D.C. Not long after, Babcock was assigned to the office of the provost marshal general where he examined passes.

On March 1, 1862, less than a year into the conflict, Babcock was offered a position in Pinkerton’s Secret Service and the Army of the Potomac — a move that redefined his role in the war. As McClellan prepared for his peninsular campaign, Babcock’s primary task was to sketch enemy fortifications from intelligence provided by deserters, prisoners, and spies. He became a skilled interrogator of the captured Confederates and created detailed and accurate depictions of the Confederate lines.

Aerial technology impacts mapping of Confederate fortifications

About the time Babcock joined the Secret Service, the Army of the Potomac began making regular use of real-time aerial reconnaissance through the newly formed U.S. Army Balloon Corps helmed by Chief Aeronaut Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. The Balloon Corps accompanied Major General George B. McClellan on his campaign up the Virginia peninsula, and Lowe used hot air balloons to observe enemy movements and gather tactical intelligence.

Union Army Brigadier General Fitz John Porter accompanied Lowe on one flight to a height of 1,000 feet, gaining an unprecedented view of the battlefield near Richmond. As soon as they landed, Porter gathered generals and mapmakers to draw up maps showing the Confederates’ fortifications based on their aerial observations.

On June 14, 1862, Lowe once again went aloft near Richmond carrying a map prepared by Babcock and E.J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton’s nom de guerre), based in part on the prewar map by James Keily and included up-to-date military information, such as Confederate batteries and Union lines as well as Union cavalry and infantry pickets.

Lowe noted, “The red lines represent some of the most important earthworks seen this morning and are located as near as possible, as is also the camps in black ink. As soon as I can get an observation from the Mechanicsville balloon, I can make many additions to this map.” The collaborative effort provided vital information for the impending Confederate attack during the Seven Days Battle, which began at the end of June that year.

Babcock’s strategic contribution — mapping the battlefield

Babcock’s exceptional map-making skills caught the attention of Union officers, who found his abilities superior to those of the Union’s topographic engineers. Pinkerton began sending Babcock on scouting missions into enemy territory — often coming under fire to map small sections of the terrain. Despite the inherent risk, he displayed an extraordinary talent for capturing the Confederate order of battle.

Babcock employed a meticulous approach to mapping enemy fortifications and positions following reconnaissance operations, ensuring first-hand accuracy. He not only scouted and mapped sections of terrain, but he also focused on mapping localized areas at the army's forefront while incorporating data from other reporting streams. He consolidated these individual maps into a comprehensive final product and added elements from published maps of the area.

These highly detailed and accurate maps were reproduced with the help of a photographer and distributed to brigade-level commanders across the entire army, giving them an enhanced tactical understanding of the terrain and enemy positions. Babcock’s work became the new benchmark within the military.

A new era as a civilian intelligence analyst

Shortly after the Antietam Campaign in the autumn of 1862, General McClellan was replaced by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside as the head of the Army of the Potomac. Pinkerton resigned his field position and undertook a new position investigating and exposing fraudulent claims against the United States during its most challenging and perilous times. By 1865, Pinkerton had severed all connection with the Secret Service of the United States.

In 1862, Babcock was mustered out of the service and initially planned to return to Chicago to continue his career in architecture. However, Burnside — a friend from Chicago — recognized Babcock’ s invaluable contribution and asked him to take over Pinkerton’s position as a civilian contractor with an honorary title of “Captain” and a salary of $250 per month. Babcock remained with Burnside for two months, focusing entirely on Burnside’s directive of reconnaissance and espionage without exploiting other sources of information.

In early 1863, Burnside was replaced by Major General Joseph Hooker. At Hooker’s request, Babcock prepared a comprehensive report outlining the responsibilities of the Secret Service Department. Hooker passed on reports to Major General Marsena R. Patrick, the provost marshal general, who ordered the formation of the Bureau of Military Information (BMI), a reorganization and expansion of Pinkerton’s Secret Service, under the supervision of Colonel George Sharpe. Due to his extensive knowledge of the Confederate army, he became one of Sharpe’s most reliable and trusted subordinates for the remainder of the war, serving as principal interrogator and leading intelligence analyst.

While the Secret Service under Pinkerton received some discussion and criticism from historians and Civil War aficionados over the years for potentially overestimating the number of Confederate troops at some locations, Babcock refined his order of battle techniques. In one report, he came within one percent of actual figures, and in another within two percent.

Post-war accomplishments

After the Civil War, Babcock returned to his architectural roots and moved to New York City. As a lifelong rower, he helped establish the New York Athletic Club and invented what may have been the first indoor rowing machine. He was one of the first inductees to the New York Athletic Club Hall of Fame when it opened in 1981.

Babcock passed away on November 20, 1908, leaving behind a legacy of bravery, intelligence, and remarkable contributions to the Union Army during the Civil War. His skills as a scout and mapmaker were instrumental in shaping military strategies and influencing the fortunes and lives of thousands.

Our founder, Allan Pinkerton, and his team of Secret Service Scouts and Spies played a critical role in gathering intelligence during the U.S. Civil War, providing a tactical advantage on the battlefield. Skilled in reconnaissance and surveillance, they navigated enemy territory, monitored enemy movements, and gathered crucial information that aided military decision-making.

Pinkerton “scouts” still play a crucial role. Organizations today rely on our research and intelligence to help shape their strategies, identify vulnerabilities, and anticipate threats, ensuring the success and safety of their operations across diverse environments. Trust in the Pinkerton legacy, and let our scouts guide your due diligence process today.

Sources

Babcock, John C. Map exhibiting the approaches to the city of Richmond prepared for Maj. Gen. Geo. B. McClellan, U.S.A. [S.l, 1862] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/99448488/>.

Arnold, Blumberg. "Civil War Intelligence." Military Heritage, Jan. 2016, Volume 17, No.4. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/civil-war-intelligence/. Accessed 3 November 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. "Seven Days’ Battles". Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 Jun. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Seven-Days-Battles. Accessed 3 November 2023.

Francis Trevelyan Miller, editor in chief; Robert S. Lanier, managing editor. The Photographic History of the Civil War. New York: The Review of Reviews Co., 1911.

Gould, Kevin. "Balloon Corps". Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balloon-Corps. Accessed 3 November 2023.

"Intelligence in the Civil War." Central Intelligence Agency, Jun. 2007, www.cia.gov/resources/publications/intelligence-in-the-civil-war/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

New York Athletic Club, www.nyac.org/web/pages/hall-of-fame. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

Stewart, Lori S. "Pvt. Babcock Joins Pinkerton's Intelligence Organization." U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence, 1 Mar. 2022, https://www.dvidshub.net/news/415560/pvt-babcock-joins-pinkertons-intelligence-organization. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.