This blog is a part of our series, "Perspectives in Crime" where we explore leading academic studies that touch on crime data.

The economic burden of crime in society is typically calculated in direct losses suffered by victims in terms of:

- Medical Care Costs

- Lost Earnings

- Loss or Destruction of Property

- Expenditures on Police Protection

- Expenditures on Correctional and Judicial Services

Less typical in economic valuation efforts are the indirect losses suffered by victims and crime-burdened communities such as:

- Psychological Distress

- Decreased Quality of Life

- The Erosion of Trust and Confidence in Authorities

“The Effect of Local Area Crime on Mental Health”

In their 2016 paper, “The Effect of Local Area Crime on Mental Health” Christian Dustmann and Francesco Fasani measure the mental distress of residents in response to local criminal activity.

The study examines the impacts of crime across many dimensions of mental health, identifying three primary channels - 1.) measurement of anxiety and fear of victimization, 2.) the loss of freedom resulting from changes in behavior to avoid being victimized, and 3.) the need to plan/invest in strategies to avoid victimization.

In the years captured by the study (2002-2008), total recorded crime in England and Wales decreased 24%, primarily driven by a decrease in property crime. Despite these reductions in crime, most households completing the British Crime Survey believed that total crime rates had increased at the national level. Intriguingly, respondents had a more accurate perception of whether crime rates increased or decreased in their own neighborhoods.

Respondents in regions with higher crime typically reported higher levels of concern regarding crime. Respondents in areas with lower crime typically reported greater satisfaction in policing authorities. Dustmann and Fasani used the British Household Panel Survey and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing to gauge mental health outcomes, linking individual respondents highly granular local crime statistics. The combination allowed researchers to distinguish the effects of various crime types on mental health.

Controlling for individual risk factors linked to mental health, Dustmann and Fasani show that local criminal activity in urban areas across England and Wales negatively affects the subjective well-being of resident populations. Strikingly, the measured impact of crime on subjective well-being was about 2-4 times larger than the impact of local unemployment. Of the many crime types examined, burglary, car theft and vandalism were the most significant drivers of local mental health. While violent crimes appeared less impactful locally, the mental health costs of violence appeared to ramify nationally.

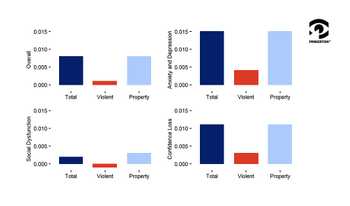

Analysis involving the disaggregation of the General Health Questionnaire into confidence loss, social dysfunction, and anxiety and depression revealed the specific pathways through which crime impacts mental health in local areas. Figure 1 shows the measured impact of crime on overall mental distress, as well as the subcategories of anxiety and depression, social dysfunction, and confidence loss. All general health measures are normalized between zero (least distressed) and one (most distressed).

The results in Figure 1 show that an increase in local property crime increases overall mental distress, weakens confidence, and substantially increases reported levels of depression and anxiety in urban residents.

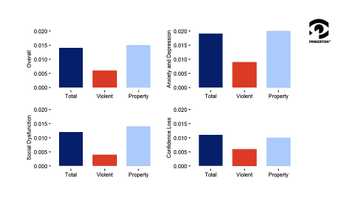

Dustmann and Fasani additionally analyzed the same data through the scope of larger aggregate areas (Police Force Areas). Figure 2 demonstrates the same measured impact of crime on overall mental distress, as well as the three clinically meaningful mental health domains. All General Health Questionnaire measures are normalized between zero (least distressed) and one (most distressed).

As demonstrated by Figure 2, through this larger geographic scope, the impacts of violent crime on mental health become more significant, demonstrating that anxiety and depression and confidence loss caused by violent crime travel greater geographic distance.

The mental health impact of mass violence and terror attacks

The study period happened to encapsulate the 2005 London Bombings, involving a coordinated series of suicide attacks on London’s public transport system that killed 52 people and injured about 700. British Household Panel Survey interviews were conducted throughout 2005, with a large break in testing in the summer months, so some respondents were interviewed in the months prior to the London Bombings or a few months after. This coincidence presented Dustmann and Fasani with an analytic opportunity to study how mass violence affects the mental health of populations distributed across urban localities of varying size.

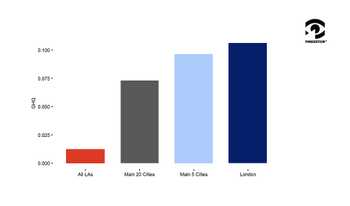

Focusing on this episode of mass violence, Dustmann and Fasani found that mental health deteriorated nationwide in the aftermath of the London Bombings. As shown in Figure 3, this costly impact on mental health nationwide increased as they restricted analysis to the 20 largest cities in England, and then to the 5 largest cities, and finally to London itself.

The measured costs of mass violence were heightened among urban residents and persons exposed to the terrorist attack in London. The primary mental health effect was realized in higher levels of anxiety and depression, with additional impacts on measures of social dysfunction. In terms of the size of the impact, Dustmann and Fasani calculate that the impact of local crime is about one seventh of the impact of the London Bombings on mental health.

The mental health impacts of crime are an underappreciated cost of crime in society. Dustmann and Fasani’s analysis show that local property crime, in particular, imposes a larger penalty on mental health than the more well-known mental health effects of area unemployment. They also show that episodes of mass violence like the London Bombings of 2005 can produce nationwide effects in higher levels of psychic distress that echo for many months after the event itself. From an economic standpoint, depression and anxiety are known to decrease labor productivity as reflected in higher rates of worker absenteeism. As Dustmann and Fasani show, this intangible cost of crime is borne by more than the direct victims of crime but also by the community at-large.

Sources

Dustmann, C. and Fasani, F. (2016). The Effect of Local Area Crime on Mental Health. The Economic Journal. 593: 978-1017.