The Old West, also known as the Wild West or Frontier Era roughly spanning from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to around 1910, is characterized by westward expansion, the settlement of the frontier, and an era where cowboys and outlaws became legends.

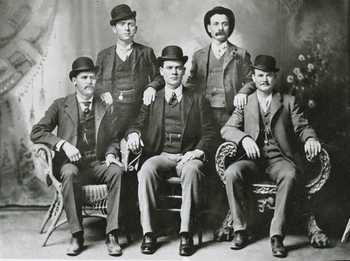

Amidst this backdrop one photograph stands out: the Fort Worth Five featuring five members of The Wild Bunch, one of the most notorious holdup collectives that ravaged railroads and banks in the Western States for roughly five years in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In 1999, the Smithsonian Institution underscored the photograph's significance by declaring it the most iconic image of the Wild West. The image, now housed in the National Portrait Gallery, was donated in 1982 by Pinkerton, whose legacy is deeply entwined with the fabric of American history.

The photograph itself evokes an image of the cultural mythology that arose from the events and lifestyle of the time — but it doesn’t tell the real story behind that photo and how it broke open a manhunt, helping to close the chapter of the Wild West hold-up men.

The beginning of the end

At high noon on Wednesday, September 19, 1900, three men rode into the Wild West railroad town of Winnemucca, Nevada with their eyes set upon the First National Bank.

Within minutes the men were inside the bustling bank, unsuspecting customers and employees going about their business. Unmasked, they drew their guns — two revolvers and a Winchester rifle — and took control. With threats of violence hanging heavy in the air, Bank President George S. Nixon was forced to open the vault and fill their sacks with a staggering $32,640 in gold coin. The robbers then took the money and left the bank by the back door, pushing Nixon, his employees, and the customers who were in the bank at the time into a fenced enclosure behind the bank to prevent passersby from seeing what was happening and prevent an immediate alarm from being sounded.

The outlaws mounted their waiting horses, and then with shots fired into the air, the robbers fled. A short distance later, one of the robbers dropped his bag of gold. He stopped to retrieve it, nearly costing them their lead as one bandit struggled to remount his spooked horse.

The entire heist was over in a breathless five minutes.

A posse was organized at once and pursued the fleeing the outlaws. Even a locomotive was pressed into service to follow the outlaws, who traveled along a road paralleling the railroad tracks. The road and tracks eventually diverged, and after first a few ineffective shots, the locomotive returned to Winnemucca. The outlaws hopelessly outdistanced their pursuers.

The Manhunt

First National Bank of Winnemucca was a member of the American Bankers Association and under the purview of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. After a thorough investigation, the Pinkertons determined the robbery was the work of three members of The Wild Bunch. Two of the men were identified as Robert Le Roy Parker, alias George Parker, better known as “Butch Cassidy” and Harry Longbaugh, alias “The Sundance Kid.”

There are conflicting reports on the identity of the third man who was believed to be the formidable Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan, newcomer Will Carver, or the fearless Benjamin “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick, a 6’2” daredevil who declared he would never be taken alive. While it seemed unlikely that the third man was Kilpatrick because eyewitnesses said all the robbers were men of average height between 5’7” and 5’10”. As for other identifiers, two bank employees said he had a scar on one side of his cheek, something akin to a wrinkle, and all eyewitnesses agreed that the third man had a determined look and smelled like a polecat.

Some alleged that Kilpatrick was a fourth man waiting along the escape route with fresh horses, although there is no credible evidence that he was involved in this robbery.

Nonetheless, every member of The Wild Bunch was wanted by the law, hunted for their individual crimes as well as those they committed together. It should be noted that while law enforcement was keenly aware of the names and identities of the outlaws, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were not as widely known as other members of the Wild Bunch.

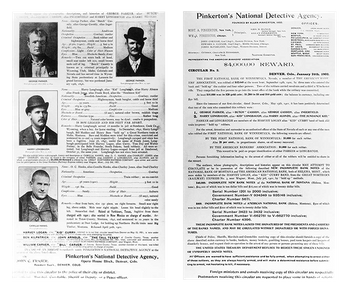

The Pinkertons printed circulars and distributed them to all local law enforcement agencies throughout the Western United States, describing the outlaws and offering a hefty reward, backed by the bank.

The Outlaws

After the robbery, the Wild Bunch needed a place to hole up for a while. Their habit was to escape from the scene of their crimes to an isolated part of the sparsely populated country — notably Hole-In-the-Wall, a naturally-formed fortress with a singular entrance, located in Northern Wyoming, just south of the Montana state line, west of the Big Horn Mountain, and east of Yellowstone National Park.

Because the robbery was of a national bank, local, state, and federal law enforcement were on the case, making their usual escape routes and hideout inaccessible.

Five members of the Wild Bunch — Cassidy, Longabaugh, Carver, Logan, and Kilpatrick — found themselves in Fort Worth, Texas, a city of 27,000 people and two train stations, for a mix of reunion and introductions. Despite their notoriety, they had not all previously pulled heists together.

The men could have easily slipped into town unnoticed, however, they were flush with some $32,000 in gold coin burning through their coveralls. Hell’s Half Acre, Fort Worth’s 22,000-square-foot, two-and-a-half acre red-light district, became their playground. Inside those 15 city blocks, they indulged in the city's nightlife and the company of women, spending their ill-gotten gains quite freely.

Undone by their own doing

Then on November 21, in what would prove to be a significant misstep, they impulsively decided to have a formal portrait taken at a local studio. This decision, possibly influenced by alcohol, resulted in that iconic photograph, "Fort Worth Five." That same photo was later dubbed by the Pinkertons as “the bad luck photo” because, well, because it led to the gang’s downfall.

Little is known about exactly what happened that day. One report stated that the men wanted to hit the saloons — Hell’s Half Acre had 20 of them — starting with expensive new clothes. Another report stated that during a friendly scuffle, some of the felt hats the gang wore were damaged and they went to a Fort Worth clothier — likely the reputable Washer Brothers. (Hell’s Half Acre was no resort town. It was known for rowdy dance halls and gambling houses and all the personal conflicts that could arise from such situations, like fistfights, knife fights, and gunfights.)

Both reports could be true, but we know that the now fine-dressed outlaws, having traded their dusty coveralls for suits, saw some derby hats in the window at the clothier. According to Pinkerton’s case notes, the five men decided, as a jest, to attire themselves in this headgear, which was somewhat unusual in the West at that time.

Elaborating on the joke, Logan, Cassidy, Kilpatrick, Longbaugh, and Carver decided to have their photo taken as a group. They went to photographer John Swartz’s gallery at 705½ Main, located above the John P. Sheehan Saloon, just a couple of blocks north of Hell’s Half Acre.

A snapshot into outlaw infamy

The result was impressive.

Pinkerton case notes state, “Sitting demurely in the front row of the picture were Longbaugh, Kilpatrick, and Cassidy, while standing staidly to the rear their hands reposing in the approved group manner on the shoulders of those in the front were Carver and Logan.”

After the sitting, Swartz made a copy for himself and hung it in his main gallery. Although it is unclear who saw the photo first, Fort Worth Police Detective Charles R. Scott, who maintained the department’s “Rogue’s Gallery” or Fred Dodge, a Wells Fargo detective posing as a gambler, the photo was sent to the Pinkerton’s office in Denver, CO, where agents stated it was their first real break in the case. By May 15, 1901, a new circular featuring the faces of Cassidy, Longbaugh, and Logan was printed and widely distributed to law enforcement in North and South America.

A persistent and organized effort had never been made to apprehend or disperse them,” said Robert Pinkerton. “We finally determined the identity of their members and succeeded in obtaining minute descriptions of all and photographs of some. Circulars bearing the true names and aliases of these suspects, and also giving descriptions, general information as to their associates, haunts, crimes, and manner of escape after perpetrating their crimes, were prepared by us and sent to the police authorities, sheriffs, marshalls, and constables throughout the United States. – Pinkerton, Essays on The Wild Bunch

Circulars were also widely distributed around-the-world, wherever the Pinkertons thought the hold-up men would take refuge.

The Agency also reproduced headshots of each individual outlaw to add to the Rogues Gallery. (These headshots as well as the original photo were safely stored in Pinkerton’s files until they were gifted to the Smithsonian Institute in 1982.)

Eventually, the Fort Worth Five and the other members of The Wild Bunch, including those not pictured were inevitably caught. By August 1904, only Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid at large. And we know how their story ends.

Harried by the constant fear of arrest with the certainty of facing a long-term of imprisonment, Cassidy and Longabaugh fled to South America, where they became a thorn in the flesh of the authorities of Argentina and neighboring States by their robberies of banks and holdups. Harry Longbaugh’s lady friend, Etta Place, accompanied them to South America and accompanied them on their lawless expeditions dressed as a youth in trousers and jacket. Cassidy, Longabaugh, and Place were killed at San Vincente [Canton], Bolivia, early in 1909 by a contingent of Bolvian military police after a gun battle in an effort to place them under arrest. – Pinkerton, Essays on The Wild Bunch

"Butch Cassidy and the Great Winnemucca Bank Robbery." NevadaGram, 16 February 2020. www.nevadagram.com/butch-cassidy-and-the-great-winnemucca-bank-robbery/. Accessed 12 Sep. 2024.

Callard, Abby. "The Wild Bunch and More Are New Faces at the Portrait Gallery." Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, 22 March 2019, www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/the-wild-bunch-and-more-are-new-faces-at-the-portrait-gallery-18165843/. Accessed 12 September 2024.

"Celebrating 150 Years: Chisholm Trail & Hell’s Half Acre in Fort Worth." Texas Hill Country, www.texashillcountry.com/celebrating-150-years-chisholm-trail-hells-half-acre-fort-worth/. Accessed 12 September 2024.

Chaffin, Sean. "Inside Downtown's Dark Past as Hell's Half Acre." Fort Worth Magazine, 7 December 2020, www.fwtx.com/culture/history/hells-half-acre/. Accessed 12 September 2024.

"The Great Winnemucca Bank Robbery of 1900." Ely News, 22 March 2019, www.elynews.com/2019/03/22/the-great-winnemucca-bank-robbery-of-1900/. Accessed 12 September 2024.

Pinkerton, “Essays on The Wild Bunch” and “History of the “Wild Bunch” Band of Outlaws, Train and Bank Robbers.” ProQuest. https://hv.proquest.com/pdfs/102597/102597_012_0442/102597_012_0442_From_1_to_173.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2024.